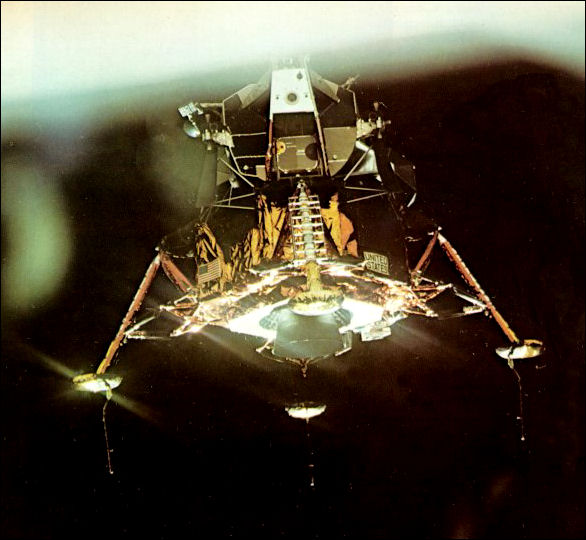

|

Leaving the ninth step of the ladder,

Aldrin jumps down to the

Moon. Earlier on the "porch" he

had radioed, "Now I want to partially

close the hatch, making sure

not to lock it on my way out."

Armstrong's dry response was: "A

good thought." On Earth his

weight, including the spacesuit

and mechanism-filled portable life-support

system, would have totaled 360 lb;

but here the gross

came only to a bouncy 60 lb. The

descent-engine exhaust bell (extreme right)

came to rest about a

foot above the surface.

|