|

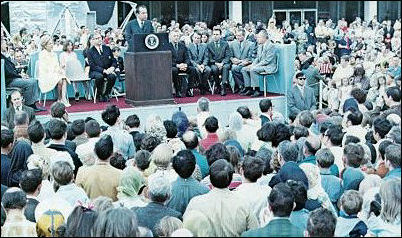

In Houston the 37th President pays tribute to the men

who performed miracles in Mission Control to save Apollo

13. To President's right are NASA Administrator

Thomas Paine and Mrs. Nixon. To his left: Flight directors

Eugene Kranz, Gerald Griffin, Milton Windler (the fourth,

Glynn Lunney, is behind lectern), then Chief Astronaut

Donald K. Slayton, James A. Lovell III (in uniform),

and Sigurd Sjoberg, Director of Flight Operations, who in

behalf of "the ground" received the Nation's highest award,

Medal of Freedom.

|