|

|

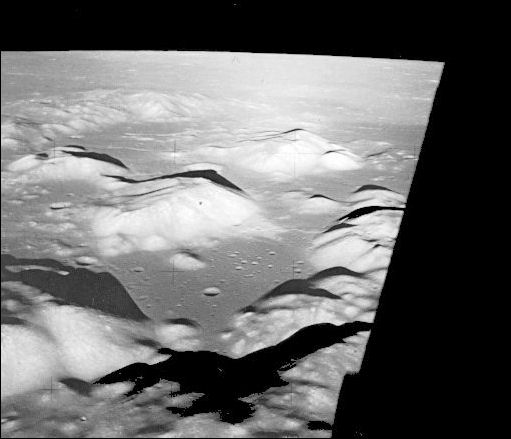

Vistas without parallel in human experience surrounded

the crews on the great voyages of exploration.

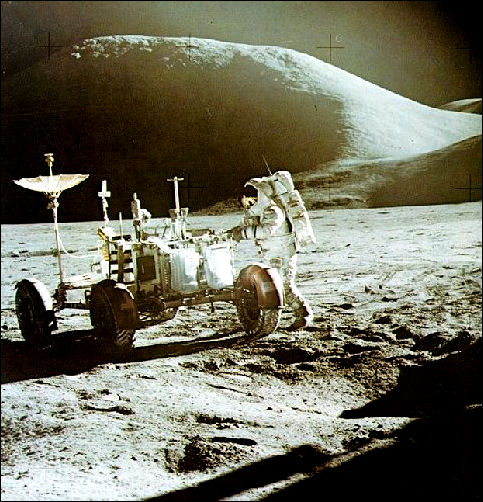

Mount Hadley, rising 2 3/4 miles above the plain,

is Apollo 15's backdrop as Jim Irwin sets up the first

Lunar Roving Vehicle on the Moon.

(Photo captions for this chapter by the author.) |