|

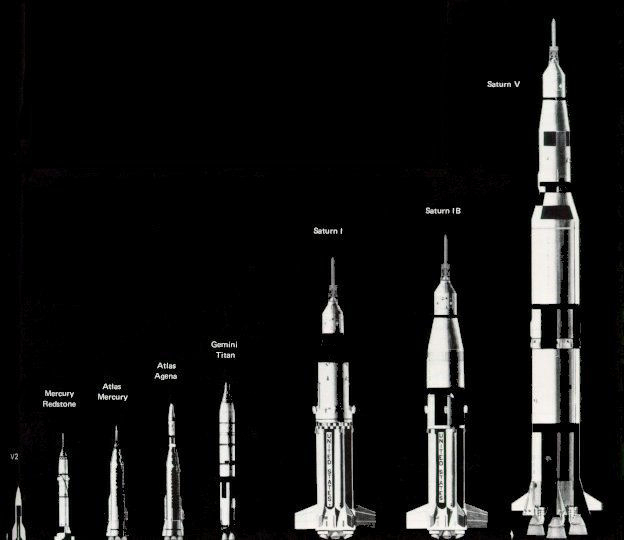

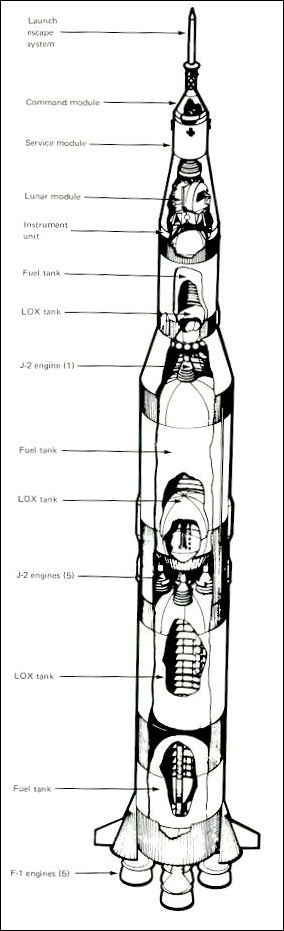

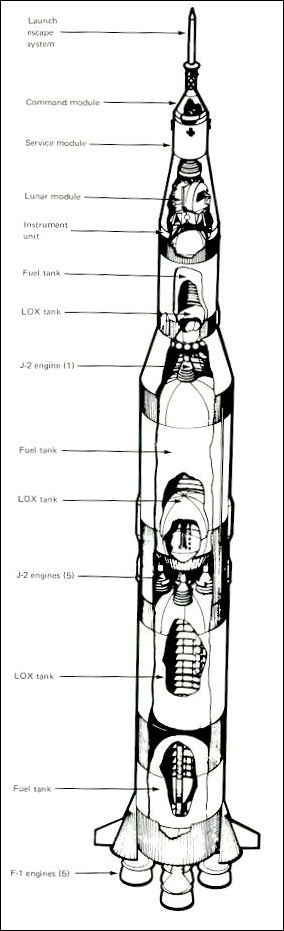

The stack: the three-stage launch vehicle, Saturn V,

surmounted by its payload, the Apollo spacecraft.

The greater part of the launch vehicle consists of

tankage for the fuel and for the oxidant, LOX

(liquid oxygen), used in all three Saturn V stages.

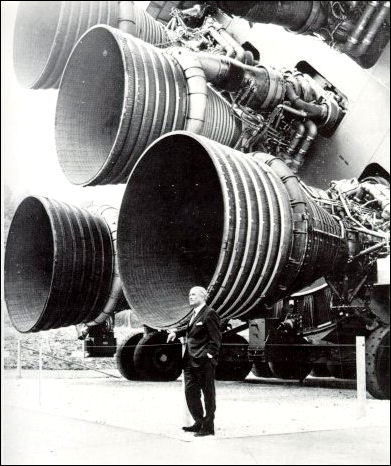

The powerful F-1 engines of the first stage burn

kerosene to produce a combined thrust of 7.5

million pounds. The fuel for the J-2 engines of the

two upper stages is liquid hydrogen. The combined

thrust of the second stage's five engines is just over

a million pounds, or five times that of the third

stage's single J-2 engine. Development of the original

hydrogen tanks was difficult because the low

boiling point of hydrogen (-253 °C) required insulation

sufficient to prevent transfer of heat from

the outside and the comparatively warm (-183 °C) liquid oxygen.

|