|

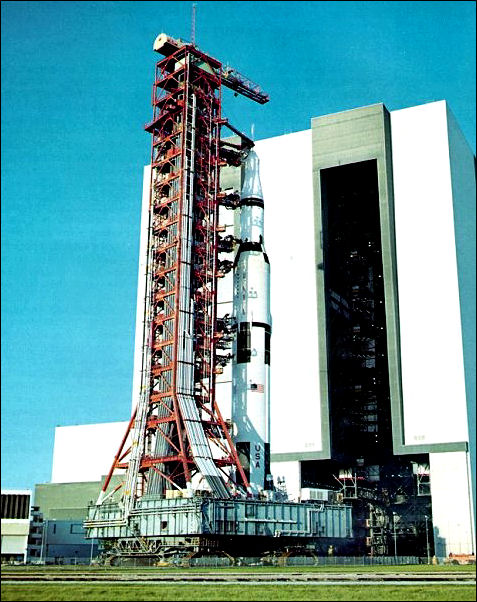

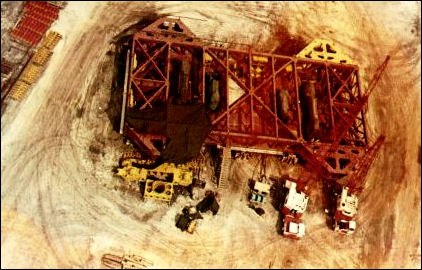

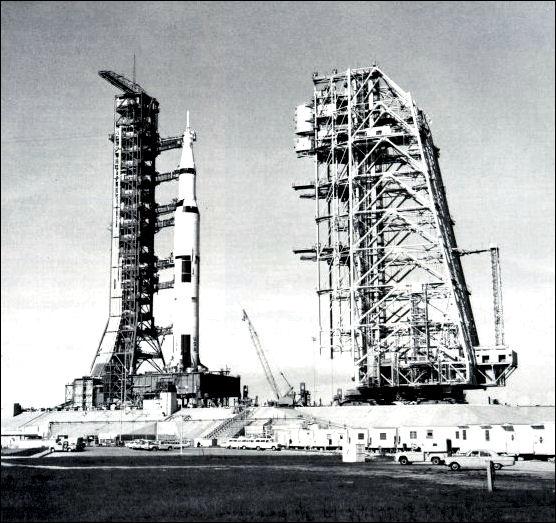

| The first Saturn V space vehicle and its Mobile Launcher on their way out to Launch Pad A atop a transporter. The pad is 3 1/2 miles east of the VAB. The Mobile Service Structure is parked at the loop where the crawlerway to Pad B diverges to the north (right). The barge canal to the VAB runs parallel to the main crawlerway. |