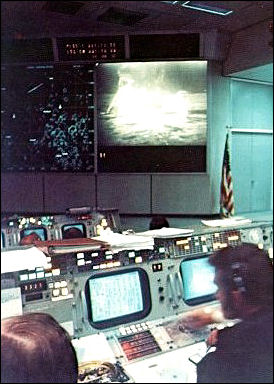

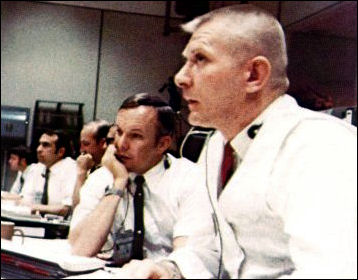

| Mission Control candid photography by Andrew R. Patnesky |

|

| Flight Director Gene Kranz watches his console display tensely as the Apollo 11 lunar module Eagle slowly settles down with its descent engine fuel supply all but exhausted. Gerry Griffin, a Flight Director during other phases of the mission, looks on in complete absorption. |