Graduated missions led confidently to a landing on the Moon

We designed seven types of missions to

test the suitability and safety of all equipment

in all mission phases. These were

designated by letters A through G:

- Unmanned flights of launch vehicles and

the CSM, to demonstrate the adequacy of

their design and to certify safety for men.

Five of these flights were flown between

February 1966 and April 1968; Apollo 6

was the last.

- Unmanned flight of the LM, to demonstrate

the adequacy of its design and to

certify its safety for men. The flight of

Apollo 5 in January 1968 accomplished this.

- Manned flight to demonstrate performance

and operability of the CSM. Apollo 7,

which flew an eleven-day mission in low

Earth orbit in October 1968, was a C

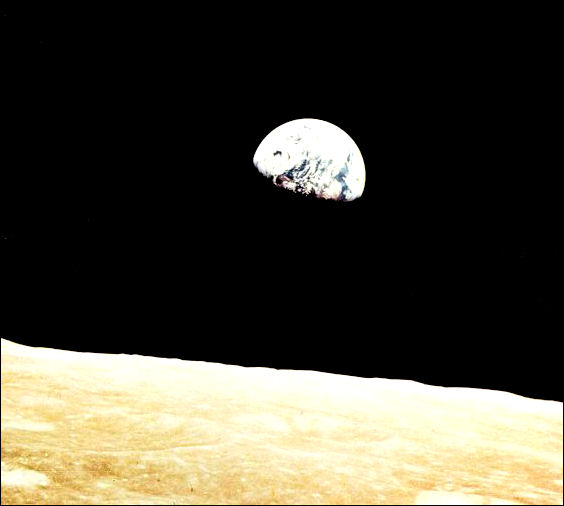

mission. Apollo 8, which flew the CSM into

lunar orbit in December 1968 was also a C

mission, but designated as C-Prime,

to distinguish it from the prior flight.

- Manned flight of the complete lunar

landing mission vehicle in low Earth orbit

to demonstrate operability of all the equipment

and (insofar as could be done in

Earth orbit) to perform the maneuvers involved

in the ultimate mission. Apollo 9,

which flew in March 1969, satisfied this

requirement.

- Manned flight of the complete lunar-landing

mission vehicle in Earth orbit to

great distances from Earth. When the time

came to commit this mission to flight, we

decided that we had already accomplished

its objectives and that it was not required.

But because this mission was in the program,

we had made detailed plans for it, and in

fact pulled much of the planning, preparation,

and training forward to use in the

Apollo 8 lunar-orbit mission.

- This was a complete mission except for

the final descent to and landing an the

lunar surface. Apollo 10, flown by Stafford,

in May 1969, was an F mission. The need

for this mission was hotly debated. Here we

would be, 50,000 feet above the Moon,

having accepted much of the risk inherent

in landing. The temptation to go the rest of

the way was great; but this mission demonstrated

the soundness of the strategy of

"biting off chunks". The training and

confidence of readiness that the Apollo 10 mission

gave the entire organization was of inestimable

value.

- The initial lunar-landing mission. This, of

course, was accomplished by Armstrong,

Aldrin, and Collins in July 1969.

- S. C. P.

|