SP-4223 "Before This Decade Is Out..."

[306]

[307] George Michael Low was born George Wilhelm Low on June 10, 1926, near Vienna, Austria. His parents, Artur and Gertrude Burger Low, operated a large agricultural enterprise in Austria. After the German occupation of Austria in 1938, his family emigrated to the United States in 1940. In 1943, Low graduated from Forest Hills High School, Forest Hills, New York, and entered Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute (RPI). His education was interrupted between 1944 and 1946 while he served in the U.S. Army during WWII. During this period, he became a naturalized American citizen, and legally changed his name to George Michael Low.

After military service, Low returned to RPI and received his Bachelor of Aeronautical Engineering degree in 1948. He then worked at General Dynamics (Convair) in Fort Worth, Texas, as a mathematician in an aerodynamics group. Low returned to RPI late in 1948 and received his Master of Science degree in Aeronautical Engineering in 1950. In 1949, he married Mary Ruth McNamara of Troy, New York. Between 1952 and 1963, they had five children: Mark S., Diane E., George David, John M., and Nancy A.

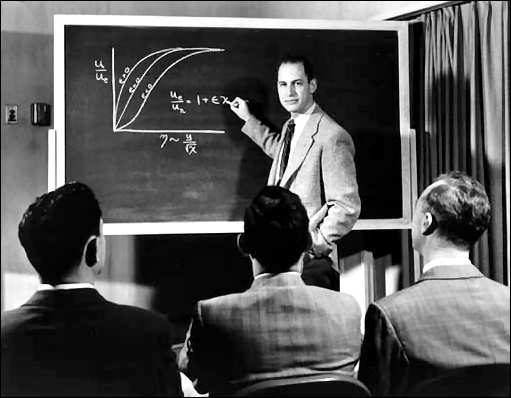

After completing his M.S. degree, Low joined the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) in 1949, as an engineer, at the [308] Lewis Flight Propulsion Laboratory in Cleveland, Ohio (now the John H. Glenn Research Center at Lewis Field). He became head of the Fluid Mechanics Section (1954-1956) and Chief of the Special Projects Branch (1956-1958). Low specialized in experimental and theoretical research in the fields of heat transfer, boundary layer flows, and internal aerodynamics. In addition, he worked on such space technology problems as orbit calculations, reentry paths, and space rendezvous techniques.

During the summer and autumn of 1958, preceding the formation of NASA, Low worked on a planning team to organize the new aerospace agency. Soon after NASA's formal organization in October 1958, Low transferred to the agency's headquarters in Washington, D.C., where he served as Assistant Director for Manned Space Flight Programs. In this capacity, he was closely involved in the planning of Projects Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. In October 1960, Low recommended that a preliminary program for manned lunar landings be formulated to provide justification for Apollo and to place the schedules and technical plans on a firmer foundation. This proposal led to his being selected as chairman of a committee that conducted studies leading to the Apollo lunar landing program, the facts of which helped President Kennedy in 1961 to declare his goal of landing a man on the moon before the end of the decade. That same year Low became deputy associate administrator for Manned Space Flight where he was responsible to the associate administrator for Manned Space Flight in the management of the Gemini and Apollo programs and the field centers directly associated with those programs.

In February 1964, Low transferred to NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center in Houston, Texas (now the Johnson Space Center), and served as deputy center director. In April 1967, following the Apollo 204 fire, he was named manager of the Apollo Spacecraft Program Office (ASPO), where he was responsible for directing the numerous redesign changes made to the Apollo spacecraft in order to get the program back on track. Low is also credited within NASA for conceiving the idea of the Apollo 8 lunar orbital flight and proving its technical soundness to others.

George Low became NASA deputy administrator in December 1969, serving with Administrators Thomas O. Paine and James C. Fletcher. As such, he became one of the leading figures in the early development of the Space Shuttle, the Skylab program, and the Apollo-Soyuz [309] Test Project. From September 1970 to May 1971, he served as acting administrator of NASA.

Low received numerous awards and honors during his distinguished career including the NASA Distinguished Service Medal (twice awarded), NASA Outstanding Leadership Award, Honorary Doctor of Engineering from RPI, and Honorary Doctor of Science from the University of Florida.

Low retired from NASA in 1976 to become president of RPI, a position he held until his death on July 17, 1984.

[310] Editor's note: The following are edited excerpts from two separate interviews conducted with George M. Low. Interview #1 was conducted while Low was deputy director of NASA's Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Johnson Space Center) in Houston, Texas, on May 1, 1964, by Dr. Eugene M. Emme, NASA historian, assisted by Mr. Jay Holmes of the Office of Manned Space Flight and Mr. Addison Rothrock, NASA consultant. Interview #2 was conducted by Robert Sherrod on January 16, 1974, at NASA Headquarters while Low was serving as deputy administrator of NASA.

Interview #1

I believe we should start our historical review of NASA's manned space flight program during the administration of President Kennedy by asking you the places and events that you had personal contact with the late President.

Unfortunately, I had only one contact with President Kennedy, and this was six days before he was assassinated. As you will recall, he visited Cape Canaveral on November 16, 1963, for a fairly brief tour. He reviewed the manned space flight program, flew over the new Cape Canaveral area-the so-called Merritt Island Launch Area (MILA)-in a helicopter, and went out to sea to watch a Polaris launching from the submarine U.S.S. Andrew Jackson.

My own part in the proceedings that day was a relatively short one. The President arrived during the morning of the 16th on the skid strip at the Cape and immediately went in a motorcade to Launch Complex 37, the Saturn launch complex. Outside of this complex we had the first Gemini spacecraft, the spacecraft that was subsequently launched on April 8, 1964.

The President's first stop on the tour was at this spacecraft, where we briefed him on the Gemini program. During this briefing, which was conducted by Astronauts Gordon Cooper, Gus Grissom, and me, we discussed the Gemini program and its current status.

I was very impressed, at that time, by the President. As I mentioned, it was the first time I had met him personally. I was particularly impressed by the questions he asked and by his detailed knowledge of the program. He had been in St. Louis, where the Gemini spacecraft was being produced, earlier in the year on September 12, 1962. At [311] that time he had been exposed to the details of the Gemini program. He recalled his visit to St. Louis and having seen the same Gemini spacecraft while he was there. He asked a number of very penetrating questions about the program and then proceeded into the blockhouse for a briefing by Dr. George Mueller [associate administrator for Manned Space Flight] on the Saturn program.

Historically, looking at the Kennedy administration and the national space program, particularly the manned space flight aspects of the national program, you had a key role in NASA's side of the work that went on, and in the historic decision announced by the President before the Congress on May 25, 1961. The decision to land an American on the moon in this decade followed a rather torturous history as far as manned space flight was concerned. It started quite apart from the hard work and problems of the Mercury program, which was coming into the launch phase of its program in early '61. President-elect Kennedy had appointed a committee, under Dr. Jerome Wiesner,1 to make recommendations to him concerning the national space program. This, in turn, followed a rather crimping budgetary treatment of Mercury and Apollo in the last Eisenhower budget.

I wonder if we might talk now about this transition period from the Eisenhower administration to the Kennedy administration and how this affected you people in the NASA manned space program. Obviously, the Wiesner report of January 10, 1961, was a detailed written report, an unclassified version of which was public knowledge two days later. It was very critical of Mercury and the NASA leadership. What about this period of transition from one administration to the other?

Before I go into details on that, I think it might be interesting to note that three years ago today, early in May 1961, four or five days before Alan Shepard's flight, most of us concerned with the manned space flight were very deeply involved in the Mercury program. We worried about the day-to-day details of that program, and our future was tied completely to the Mercury program. But we did not know whether there would be any manned space flight program....

[312]

....beyond Mercury. We did not know whether the country would support a major effort beyond Mercury in manned space flight.

Two years before, ground had not yet been broken on the Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston. As you know, there was concern there, with 2,500 people working on a day-by-day basis on the Gemini and Apollo programs. In the same time period, launch vehicle development facilities were being built in Alabama [The Marshall Space Flight Center], Mississippi [Mississippi Test Facility now Stennis Space Center at Bay St. Louis] and Louisiana [313] [Michoud Assembly Facility at New Orleans]. There were launch facilities in Florida and a team of contractors to build boosters and spacecraft for the Gemini and Apollo missions started work.

This, perhaps, paints a clear picture of what happened in a three-year period. The work leading up to that, of course, took place during 1960 and early 1961. The Space Task Group at Langley Field, the group that became the Manned Spacecraft Center at Houston, prepared preliminary plans for a program beyond Mercury, early in 1960. I don't recall the exact dates, but I believe that in the spring of 1960 the team from the Space Task Group went out and briefed all of the other NASA centers on our thoughts for manned space flight beyond Mercury.

This effort culminated in a briefing to NASA Administrator [T. Keith] Glennan on July 9, 1960. At that time we gave Dr. Glennan, Dr. Dryden, and Mr. Horner, who was then associate administrator of NASA, a description of the advanced manned space flight program as we then saw it, its scheduling implications, and its costs.

Now at that time, the program we had planned was one not leading to a lunar landing but one that would stop after the circumlunar flight.

Gemini was not in it?

Gemini was not in the picture. I was trying to recall some of the planning that occurred prior to this, in 1959 or early 1960. This was done by the Goett Committee2 . . . The Goett Committee included people like Al Eggers from Ames and Max Faget from Space Task Group. I served on it representing Abe Silverstein. There were several other people-I don't recall who they were. As I recall, the Committee deliberated whether the next major step in manned space flight should concern itself with a large space station program or a deep space program. The basic conclusion of the [Goett] Committee was that a deep space program (and by deep space I mean anything beyond earth-orbital activities) would lead to a quicker, focused advancement of the technology needed for manned space flights.

On the other hand, the [Goett] Committee also felt that making a lunar landing, or planning for a lunar landing, was a step which was [314] too far beyond what we were willing to talk about at that time. So the recommendation of the Committee was that the manned space flight effort of NASA should be focused on a circumlunar flight.

Out of this Committee's recommendations, the Space Task Group prepared a program plan. They presented this plan, as I mentioned before, to the NASA Research Centers, with primary emphasis on informing the centers of the kinds of research which should be carried on to make such a program possible.

Who was Chairman of the Space Task Group [STG] team?

Bob Piland was Chairman of the STG team. Piland, at the time, was deputy to Max Faget, who was chief of one of three divisions in STG.

Were industry studies emanated?

Industry studies did not come until later. I have here copies of some of the slides that were used in this briefing to the centers. This effort culminated in the presentation I mentioned earlier, to Dr. Glennan, Dr. Dryden, and Mr. Horner on July 9, 1960. At that time Dr. Glennan gave preliminary approval to the program. The briefing was also conducted in the context of a forthcoming NASA-Industry Conference and the material which I was to present.

The general subject of the NASA-Industry Conference was to describe industry studies we would soon request for a circumlunar flight program, but at the same time to inform industry that we had no approval for the program beyond these studies; that we were, at this time, only talking about a study effort . . .

At the meeting on July 9, the name Apollo was approved for the program. I had already prepared my paper for the NASA-Industry Conference before the meeting on the 9th, and later added a comment, "and we will call this program 'Apollo.'"

Now remember, at this time we still were talking about only circumlunar flight. In fact, we said Apollo was a program with two avenues of approach-one of them, the main stream, being the circumlunar flight program. We had planned a program that, within this decade, would lead to a circumlunar flight; beyond this decade, [315] Apollo would eventually lead to a lunar landing and to planetary exploration. We also proposed that, within this decade, Apollo could lead to, or could be part of, the space station program . . .

At the time we had people at Space Task Group considering what we could do beyond Mercury. I don't think we were seriously thinking about Mercury Mark II, which later became the Gemini program, until the summer of 1961. The Gemini program was approved in December 1961. Also, you must remember that most of us at the time were spending full time on Mercury, and very little time was available to consider what would happen beyond Mercury. I mentioned that Bob Piland was the sparkplug for Apollo at the Space Task Group, and I doubt that he had more than two or three people working with him on future programs out of the total people assigned to the Space Task Group.

In Washington, we had a very small group in Manned Space Flight. The only one in Washington who really spent any time on advanced programs was John Disher, and he probably didn't spend more than ten percent of his time on that because he was also involved with the Mercury program. So this was strictly an extracurricular activity which we fit into whatever time we could spare from the Mercury program. This was true of Bob Gilruth and his top people and of all the people here in Washington, I'm sure.

That brings us, roughly, through September 1960. Were the future programs or goals of NASA discussed at the Williamsburg Conference?

I was not at the Williamsburg Conference . . . I believe others can speak on that much better than I can. While the studies for the circumlunar flight were going on, we became concerned again as to whether we were going far enough with the circumlunar flight or whether we should really focus our attention on a lunar landing.

I had forgotten about a memo which my secretary [Mrs. Lillian Stutz] dug out for me this morning, which I will read to you. This is a memo dated October 17, 1960, for the director of Space Flight Programs, Dr. Abe Silverstein, on the subject of the manned lunar landing program.

[316] Paragraph 1 states, "It has become increasingly apparent that a preliminary program for manned lunar landings should be formulated. This is necessary in order to provide a proper justification for Apollo, and to place Apollo schedules and technical plans on a firmer foundation."

The memo went on to say in paragraph 2, "In order to prepare such a program, I have formed a small working group consisting of Eldon Hall, Oran Nicks, John Disher, and myself. This group will endeavor to establish ground rules for manned lunar landing missions, to determine reasonable spacecraft weights, to specify launch vehicle requirements, and to prepare an integrated development plan including the spacecraft, lunar landing and take-off systems, and launch vehicles. This plan should include a time phasing and funding picture and should identify areas requiring early studies by field organizations.

Paragraph 3 . . . "At the completion of this work we plan to brief you and General Ostrander on the results. No action on your part is required at this time. Hall will inform General Ostrander that he is participating in the study." Signed by George M. Low, Program Chief, Manned Space Flight. And there is a notation under it in pencil, "Low, O.K.," signed "Abe."

What was your motivation for this particular memo? What triggered it?

I knew you would ask that question, and I don't know.

It was just a sense of timing?

This was the time, of course, that we were beginning to discuss with industry what the Apollo program was. We were also quite concerned, of course, that in the subsequent year's budget, which was being prepared at that time, there were insufficient funds for any major lunar program. And we felt it would be most important to have something in the files, to be prepared to move out with a bigger program should there be a sudden change of heart within Government, within the administration, as to what should happen. This memo (I was just looking at the date) was [317] written during the Eisenhower administration and before Election Day.

We really have two main historical paths from here on out. One is the President's Scientific Advisory Committee (PSAC) and its role with regard to Mercury, which becomes more prominent with the new administration, and the other is the whole process of the lunar landing decision and how that came about in May. Do you think we can develop these two themes chronologically, or should we take one story and then do the other?

It would be easiest for me to discuss what happened within NASA in the lunar program and then go back to discuss what happened with Mercury at the same time, because PSAC was involved in that.

Now, one reaction before I forget. The people we talked to have said there was a general uncertainty existing in NASA in the December-January-February period.

Yes, and I think we all felt this quite keenly. As you know, the last Eisenhower budget carried a paragraph which said we'll complete Mercury and then future studies will be needed before we could decide what else we could do in manned space flight.

Was Dr. Glennan the only one carrying to the Bureau of Budget and the White House the thought that had gone into future manned missions? How was the Eisenhower budget determined? Did Glennan give you the planning go-ahead right from the start in July?

In July, we had the planning go-ahead. I believe Dr. Glennan, Dr. Dryden, and Dr. Seamans, who had joined the organization in the summer or fall of 1960, carried the story forward to the Bureau of the Budget.

The next major step in the planning within NASA was essentially an outgrowth of the Space Task Group that I formed on October 17, 1960. We put together a preliminary story during November and [318] December, 1960, and on January 5, 1961, presented the program for manned lunar landing to the Space Exploration Council of NASA. This Council, I believe, consisted of the directors of the major centers and Dr. Glennan and his immediate staff in Headquarters.

This was a full day of briefings?

This was a full day of briefings, following general guidelines which were developed by this initial small task team I had. There were briefings by the Space Task Group; Mr. Faget made a presentation; and Dr. von Braun made a presentation for the Marshall Space Flight Center.

The presentations showed that there were major disagreements within NASA as to how the problem of a lunar landing should be approached. The people at the Space Task Group were primarily interested in the so-called direct approach of going to the moon while the Marshall group felt very strongly that an earth orbit rendezvous approach should be used.

At the same time, of course, John Houbolt of Langley Research Center was developing his lunar orbit rendezvous approach, but I don't think this was described in any detail at the January meeting . . .

It was something we were all aware of. We knew Houbolt was working on it, and occasionally people told us about it, but at first nobody thought it was a worthwhile approach. This, historically, was the case with everybody who looked at it. We were horrified at the lunar rendezvous approach the first time we saw it, and it was only after we studied it in depth, as Houbolt was doing at the time, that we became convinced that this was really the way to go.

Were you discussing the lunar orbital mission, or were you really focused on the lunar landing in this January 5 meeting?

In the January 5 meeting, the title of the presentation was, "A Program for Manned Lunar Landing," so it was an effort on January 5 to show top NASA management what could be done to extend the then-existing Apollo program to a manned lunar landing program. But it was sort of a diversified . . .

[319] When you say "then-existing Apollo program," the Apollo program at that time was a proposal, a series of studies being done by industry, wasn't it? And that was what Eisenhower had cut out of the budget just the same month, wasn't it? Or maybe it was just before or after that?

It was a series of studies proposed to industry. I believe we were supposed to spend no more than a million dollars, and the goal of these studies was circumlunar flight. This is a point I can't emphasize too strongly, that the studies ended with circumlunar flight and not with a lunar landing.

It is very important to stress that this was a lunar landing program examination at the January 5th meeting as distinct from the Apollo studies, which were circumlunar studies. Had you gone over the Air Force studies, the contract studies on lunar landings, to any extent?

The people on my task force had gone over this. In fact, I think we assigned one of our people to review these studies. I don't remember them in any detail, however. One recollection I have of the meeting is that Dr. Glennan listened very politely, as he always did, but emphasized at the end of the meeting that we had absolutely no authority to go ahead with any program beyond the Mercury program, except for the studies for the Apollo circumlunar program; that he could not really authorize us to pursue these matters any further. He put a heavy damper on this entire effort. His function then, of course, was to carry out the wishes of the administration, which had been that there would be no major emphasis on manned space flight following the Mercury program.

The minutes of that meeting, which are very terse and general, do show that he placed that on the record. Nevertheless, did the Saturn program continue at that time?

Yes, but not beyond the Saturn I program. They were developing the second stage but weren't developing any advanced Saturn [320] hardware. The C-2 was merely in a study phase. Since my main association at that time was with the spacecraft end of it, I probably slighted the launch vehicle, and I'm glad you mentioned this. I think one of the most important decisions in the whole lunar landing program was NASA's decision, and I probably should say Abe Silverstein's decision, to base the future launch vehicle programs on hydrogen technology for the upper stages. This, at the time, was a very daring decision.

What was that approximate date?

I would say 1959. You'll find that when the decision was made to have the second stage on the Saturn I, the second stage then was hydrogen. I think it happened in December 1959. It became public knowledge a short time later. When the budget was presented to Congress in early January 1960, they asked for a supplemental appropriation to get the J-2 engine program going. But remember, at that time there was no J-2 engine. The RL-10 engine was not working too well. [It has turned out to be an excellent engine now.] And we really knew very little about insulation and bulkheads and all of these problems. Yet the decision was made by a committee chaired by Silverstein to base the whole future launch vehicle program on hydrogen technology. It was really one of the most important decisions in the program, one of the key decisions that allowed us to go ahead with the Apollo lunar landing program in 1961.

Is there anything more as a consequence of this January 5 meeting?

As a result of this meeting, Dr. Seamans established the Manned Lunar Program Planning Group. This planning group met for the first time on January 9, 1961. Again I was chairman of that group. Members were Oran Nicks, E.O. Pearson, Al Mayo, Max Faget, Herman Koelle, and Eldon Hall. The purpose of this group was to prepare a position paper which would answer the question, "What is NASA's Manned Lunar Landing Program?" This group met almost full-time for a week or two and prepared a report which was presented in final form to Dr. Seamans on, I believe, February 7.

[321]

In this group we had representatives who favored the earth-orbital rendezvous approach; we had others who favored the direct approach to the moon. Again, Houbolt was not represented. We did assign to one of our members, however, the task of studying and looking into Houbolt's approach and studying the lunar orbit rendezvous method.

He came back later and said he had studied it and his basic conclusion was that the lunar orbit rendezvous method would not work . . . It was Max Faget who did this study, and based on his preliminary look, it did not appear to be an appealing approach. Max, at the time, was strongly in favor of the direct approach to the moon. A year or so later, Max Faget himself became one of the strongest proponents for the lunar orbit rendezvous approach, so it's interesting to see that outstanding technical people do change their minds and their conclusions occasionally . . .

I think we were fortunate in a number of areas to have people in the agency with the foresight to start hardware in critical areas. The F-1 engine, the Saturn I booster, and the hydrogen decision [322] were the three things that allowed us to jump in with both feet in May 1961. Without those we couldn't have done it.

I'll come back to the Mercury program. Gagarin's flight was on April 12, 1961. On April 12 there was sudden interest again, in this country, in manned space flight. On April 11, the day before Gagarin's flight, I was in the middle of a presentation to the House Committee on Science and Astronautics, which was chaired by Congressman Overton Brooks [Democrat from Louisiana] at the time, on the manned space flight picture and defense of the budget for manned space flight.

I was about half way through the presentation when it was time for lunch and Committee adjournment. I had with me a movie of Ham's flight.3 Ham had flown in January, and this was a short sound film of the first flight using a chimpanzee in a manned space flight capsule that this country had made.

The Chairman said, "Let's start with the movie when you get back tomorrow." That night Gagarin flew. The next day I did not go back to complete my testimony. Mr. Webb, Dr. Dryden, and Dr. Seamans (I'm not sure whether Dr. Seamans was there as a witness or not) presented an overall picture of where we stood in manned space flight, what the Russians had done and what they could be expected to do, and what we had done.

It was probably one of Mr. Webb's first appearances before that Committee and he did an outstanding job in avoiding panic in the country by the way he presented the NASA picture on the day after the Gagarin flight. Incidentally, that hearing was not held in the normal Committee room. It was in the Caucus Room, and it was filled completely with interested bystanders.

The following day, we went back to complete my presentation of manned space flight. Dr. Seamans and I were before the Committee, back in the Committee room again. One of the things I remember was that we decided not to show the film. We thought it would not be in our best interest to show how we had flown a monkey on a suborbital flight when the Soviets had orbited Gagarin. The Chairman did say, "Well, we thought we were going to start with the movie." We looked around and the projectionist wasn't there, and we fumbled and said, "We don't have it with us today."

[323] But we did go on, and during the hearings, Representative [David S.] King of Utah noted that the Soviets were being quoted as saying they would land on the moon in 1967. He asked whether we could do it. The only background that Seamans really had at that time was the February 7 report, and under pressure he said the goal might well be achievable. This is where the 1967 date first appeared.

King gave him the 1967 date and said that was the 50th Anniversary of the Bolshevik Revolution . . . can you make it? That's the way the words were put into Seamans' mouth.

Incidentally, I'm just checking the February 7 report. it showed manned flights to the moon in the 1968-1970 time period.

Following this, then, there are a number of items in your history where Vice President Johnson asked the agency for a plan for manned space flight. The Fleming Committee was organized in about this time period. The purpose of the Fleming Committee was to get better schedule information, better cost information, following up on the February 7 report with a much larger effort to come up with more specific details of what the program should cost, how it should be done, and where it should be done.

I think it's interesting that the men on your Committee were members of the Fleming Committee.

That's right. The same people participated and carried on with the work they had done. One way of looking at it is that it went from the small Space Task Group, which I formed on October 17 [1960], to the Low Committee of January 7 [1961], to the Fleming Committee formed in April-one flowing into the other and each one giving more specific details.

And you still had not flown the first Mercury astronaut?

We still had not flown Shepard's flight. Of course, it was immediately after Shepard's flight that these things were available. The Fleming Report was by no means complete.

[324] Webb was briefed on the results around the third week in May.

But at the same time, NASA management went forward and presented the plan to the administration. This was between Shepard's May 5 flight, as I recall, and President Kennedy's speech on May 25, which gave the country, and all of us who were working on the program, the go-ahead and boost we needed.

That's a very important historical chapter we have just reviewed. It's the internal NASA work contributing to the lunar landing decision of May 1961. Does that cover it fairly well so we can go back now to the Mercury program and the transition from one administration to the other? What was the impact of the Wiesner report upon the Mercury program? That might be a way to get this kicked off . . . and then, of course, you'll want to bring out some of the problems that the program was involved with, the booster, etc.

First of all, I think I should say that we did have complete and full support during the Eisenhower Administration and under Glennan for the Mercury program. The thing I may have questioned before was the continuation of future manned space flight beyond Mercury. But there was no time in the Mercury program where we were held back because of funding, or because people told us to go slowly. In fact, the pressure was always in the other direction. It was, let's get on with Mercury.

I remember Dr. Glennan, on many occasions, driving us very hard and, of course, this feeling permeated throughout the entire Mercury program. So the impact of the change in administration on the Mercury program was a minor one in that sense, if any.

In the late fall or early winter of 1960, the Mercury program was approaching the manned space flight stage. We'd had unmanned flights on the Redstone and on the Atlas; we'd had successes, and we'd had failures. But the program was still moving along as quickly, or more quickly, than any other program had ever moved. We drew comparison curves, in connection with Gemini and Apollo. Mercury was moving exceedingly well.

[325] The first Redstone flight with a Mercury capsule was on December 19, 1960.4 There had been an unsuccessful preliminary attempt at this flight in November. We then went on with the Redstone flight in December, and the Ham flight was in January.

At about this time period also, and I don't know whether it was January or February, a number of us felt that before very long we would be ready to tell our management that we were ready to make a manned space flight, the suborbital flight on the Redstone. The flight was scheduled for about April. We felt that the administrator would have to go forward to the president and say, "We're now ready to make a manned flight." Bob Gilruth believed that if the new president were faced with this decision, not knowing the agency and not knowing the people in the agency at that time, he would be hard pressed to say, "Go ahead." He would want to ask questions: Do these guys know what they are doing? Are they really ready? Or do they just want to go ahead?

So we suggested to Dr. Dryden at the time, and this must have been in the interim before Mr. Webb came on board, that we should have a committee appointed by the president to check on the Mercury program. Dr. Dryden went to see Jerry Wiesner, who had already been appointed the President's Science Advisor, with this idea, and together they appointed a committee which was not really a President's Science Advisory Committee [PSAC], although it had some PSAC membership on it. It was chaired by Don Hornig, who is now the President's science advisor and chair of one or two panels.

It was called a Subcommittee on Manned Space Flight?

It was a special subcommittee, but it included many members who normally were not on the President's Science Advisory Committee. This Committee met in March and traveled around the country to McDonnell, to the Cape, to Langley, and to NASA Headquarters in examining the Mercury program. There were some very competent people on this committee, some who had been involved in this kind of business before, and others who had not.

I think to me the most gratifying experience was to see a man like Don Hornig, who had contributed to the Wiesner report, [326] come in with a very open mind about the program. He was an excellent chairman but also one with a fairly negative approach to manned space flight as a whole, at least initially. To see him argue, on the last day of that week, with Jerry Wiesner, and support the benefits of manned space flight, saying what a wonderful program Mercury was, was very gratifying.

You reported to the NASA senior staff meeting on March 15 that the Hornig Committee, having visited Langley, St. Louis, and AMR [Atlantic Missile Range], "had a better feeling now for the system as it is."

The Hornig Committee was the major influence of the Wiesner group on the Mercury program. Now we were at perhaps the most difficult time in the whole Mercury program. I don't have a flight schedule in front of me now, but in a period of, I think, ten days we got off three or four launches, each one of which had to be successful before we could go on with Shepard's flight.

So we were in a situation where, first of all, there was major Soviet activity leading up to Gagarin's flight. We had major difficulties with the Atlas between the MA-1 flight and the MA-2 flight, and NASA as an organization stuck its neck out with the MA-2 flight with a temporary fix to do that. We had had two Little Joe failures, and we needed a successful Little Joe flight. We had to get MR-2 off. We had landing bag difficulties with MR-2 and had to fix that. All of these things had to happen before we could fly Shepard. On top of that, we had to support Hornig Committee investigations.

How about the Russian dog flights?

One point I did not mention before is that, although the initial Hornig report appeared to be very good, some of the medical members of the Hornig Committee caucused the night before the report was made, in Washington, and turned in a very, very negative report. They recommended that we could not possibly take the risk of flying a man in a weightless flight, where he would be weightless....

[327]

....for five minutes, without many additional tests of monkeys. In fact, they wanted us to fly 50 monkeys. We learned there weren't this many trained monkeys available in the country.

Was Bob Gilruth going to transfer the program to Africa, where they have plenty of chimps . . .?

They recommended additional space flights. It was an exceedingly difficult period to try to make all of the hardware work, while at the same time satisfing a group of uninformed people as to whether or not we should go ahead . . .

But what really disappointed-I think that is the word to use-many of us who were trying to get on with the program was that this was a group of people who, we were convinced, were not really informed on what they were trying to do. They were not approaching it like Don Hornig had, in a positive manner, and they caused an [328] awful lot of difficulty at a time when we had enough difficulties. This really was the most difficult time in the Mercury program.

Until April 12 were you still really working to beat the Russians in a manned flight?

One of the deepest disappointments to me was when I got a phone call, the night of April 12, at 2 am, that Gagarin was up.

Is there anything in particular that should be put on the record with regard to the Redstone and those various problems that wouldn't already be on the record? Did you have more confidence, perhaps, in the Redstone than the Marshall people did? Wasn't it the MR-2 flight that had not followed the exact parameters precisely and yet was within the tolerances?

Very definitely at that time period there was a conflict between the booster people and the spacecraft people on whether or not an additional booster flight would be needed, and the booster people felt that they could not commit a man to the next flight. We did fly an additional Redstone flight without a spacecraft, and it was successful.

Did you have any comments to make on the post-Shepard flight and the apparent impact that the Shepard flight might have had on the president and the American people?

I recently made a comment on this subject in a paper I gave on October 1, 1963, the fifth anniversary of NASA. I just happened to be giving a talk at a technical meeting on the West Coast-a luncheon speech-and I had a comment in there about how surprised we were at the tremendous interest that the people and the press had in Shepard's flight and all subsequent flights. In a press conference following this speech, one of the reporters asked, "How naive could you have been to think that there wouldn't be this interest?" Yet I still don't think we were any more naive than the newspaper people themselves at that time . . .

[329] I was tremendously elated the day after Shepard's flight. I remember coming back to town that evening. I got into the office just before quitting time (you know, it was a short flight then), and I invited everybody and anybody that I could find to a party at my home that evening. And my wife didn't know I was in town yet. [Laughter] Then I stopped at the liquor store on my way home. It was probably one of the best parties we ever had-in Washington, at least, following any flight.

And I recall also that John Disher and Warren North and I went almost directly from the party to my office, the next morning, and we decided, "Let's put some more finishing touches on what we can do on the lunar landing program." Now what I did not know at the time was that Abe Silverstein was meeting with Webb, Dryden, and Seamans, and others, and actually spent part of that day with McNamara, being about ten steps ahead of what I was trying to do in my office. So this is the kind of impact that this made on everybody.

The culmination of this effort, of course, was President Kennedy's address to Congress on May 25, 1961, committing this nation to the goal of a manned lunar landing.

Could you discuss some of the steps taken after the decision to land an American on the moon was announced by President Kennedy on May 25? Was not the lunar landing mode the next major decision?

The launch vehicle people formulated detailed plans for the facilities they would need and for the configuration of the launch vehicles which would be needed.

On the spacecraft end, during the summer of 1961, we prepared specifications and requests for proposals for the Apollo spacecraft. These were mailed out during the summer. And this, of course, led to the selection of North American for the contract for the Command and Service modules.

Also during this time period, people here, and particularly at the Space Task Group, were doing more detailed designs of the lunar landing system, and-remember-this was a Lunar Landing [330] Stage, at the time, to go behind the Command and Service modules. We also started getting more and more interested in the lunar orbit rendezvous approach.

I'm trying to think of the timing here, and I believe John Disher could help you much more than I can about the detailed effort during this period of time. Brainerd Holmes came on board in October 1961. We discussed with him during the rest of the year various designs for the lunar landing stage, for the "direct approach" to the lunar landing. We were not really talking to him yet about the possibility of a different method or approach, because none of us had yet become convinced that the lunar orbit rendezvous method was the way to go.

I remember taking Joe Shea, who had come aboard in December 1961, to introduce him to the Space Task Group. We spent a good part of the day being briefed, by the Space Task Group and people from Langley Research Center, on the lunar orbit rendezvous approach. It was about January 1962 that Dr. Gilruth and his key people became convinced that lunar orbit rendezvous was the way to go.

Gemini was coming along at about the same time?

Gemini was coming along as an almost separate program at about the same time, with studies during the summer of 1961, the development plan prepared about November 1961, and the program being approved in December 1961.

And the booster studies were under way in the Golovin Committee during the summer of 1961?

That's right. It wasn't until December 1961, when we had the first meeting of Brainerd Holmes' Management Council, that we decided that the Saturn V should have five engines in the first and second stages. Until that time we had four engines.

I remember also, in this December meeting, Bob Gilruth saying, "Well, even if we don't go ahead with the approach we presently have planned (namely, the direct approach), we could use that extra booster power with any other approach that we would take." So he went along with it on that basis.

[331] Gilruth had become convinced in favor of lunar orbit rendezvous?

He was beginning to be, in the December 1961-January 1962 time period.

So he had LOR in mind when he was supporting the five-engine advanced Saturn?

He definitely did. I recall, at the first meeting of the Management Council, Gilruth said he was not convinced we had the proper approach to the moon, but no matter which approach, he would like to see that fifth engine in there.

Was the major pacing item the boosters? You recall that in 1961 you had the decisions on the selection of AMR [Atlantic Missile Range, now named the Kennedy Space Center] as the launching facility; you had the Michoud and Mississippi static test area. These decisions were all announced late in December 1961.

During 1961, all of the major decisions in the program were made, except the LOR decision. We committed the land and the facilities. We committed to the contractors for, I think, all of our stages except for the lunar landing or LEM [Lunar Excursion Module] stage. So the only hole that was left in the program by the end of 1961 was the way to go to the moon, and that particular stage and its modules.

I didn't appreciate until now that our first Saturn launch on October 27, 1961, preceded the first orbital flight of Glenn (February 20, 1962). I think you might want to put on the record that we really wanted to try to orbit a Mercury astronaut in the calendar year 1961, as against doing it the same year as the Russians had done it. Was there any thought like that in NASA Headquarters?

From our point of view, and I speak of both the Space Task Group and my office at NASA Headquarters, we were always very schedule conscious in Mercury, and we had set ourselves a goal of getting [332] a manned flight off in 1961. We had made these commitments and we just wanted to maintain and keep these commitments.

Unless you establish a goal for yourself in any program, whether it's going to the moon or orbiting a man, you will never make any schedules. So once we had established these goals, and once we had told the public and our management that this was what we were going to do, we were making every effort to do this. I think it was more that kind of a personal commitment we had all made as opposed to getting it off in the same year as the Russians did.

As you know, we came very close to getting Glenn's flight off in 1961. It slipped into January 1962, and then we had the weather problems in January that put it into February. But, again, I don't think I ought to apologize for any of the wonderful people working on Mercury for not making it until February, because it was still a tight schedule all the way through.

I guess the other major area we would like to cover before we conclude would be the mode decision of 1962. At what point did the arguments begin to break down and coalesce into pretty much a unanimous decision?

There were arguments at every step of the way. As I said, there was a time when Max Faget, early in 1961, was very much against this. By late 1961, he was convinced this was the only way to go, and so was Bob Gilruth. Coming into Washington after I had spent some time at Langley, I was probably starting to support and believe in this kind of a decision early in 1962.

At that time, we had organized our Systems Engineering organization under Dr. Shea, whose task it was to decide what mode to take to the moon, or how to go to the Moon, and how to synthesize the entire program. I don't know specifically when Joe and his people became convinced that LOR was the way to go.

How about the Huntsville people?

They were probably next in line. I do recall Joe Shea becoming convinced fairly early and then setting out to study this mode in [333] real depth, and Brainerd Holmes beginning to lean toward LOR in the spring of 1962. And then Brainerd, through the Management Council, and through a series of technical briefings from Joe Shea's people, convinced the Huntsville people that LOR was the way to go. In the end, the Management Council unanimously recommended the lunar orbit rendezvous approach. Shortly thereafter, the recommendation was presented to general management by the Management Council. The next step was to convince Jerry Wiesner's people that this was the way to go. It took all of that summer to get everybody convinced that this was the approach we should take. In the meantime, of course, we had prepared our contractual work statements so that we could move very quickly with a contractor selection in this area.

We'd had industry studies, we'd had in-house studies, and one by one, as people looked into this more and more thoroughly, they became convinced as we had that LOR was the proper approach.

It's been said, and I'm not sure it's true, that Houbolt almost had to publish the LOR concept in Astronautics and Aeronautics. (I think it was February or March 1962 that it appeared) to really begin to catch thinking on the lunar orbital mode. Is this true?

Well, Houbolt did write a number of letters to Seamans and to Brainerd Holmes. In fact, as I recall, one of the first days that Brainerd Holmes was on board, he was handed a very long letter that Houbolt had written to Seamans saying that we really didn't know what we were doing. John Houbolt deserves a lot of credit for being as persistent as he was in pushing this forward. I'm now convinced that he was right.

In your office, were you becoming increasingly involved with the Apollo lunar program and Gemini? What was the relative concern you still had with Mercury in 1962, or was that largely under the Space Task Group?

It became less and less of a concern, of course. Perhaps I can best describe this in terms of organization. I had a very small office at [334] Headquarters initially, and by the summer of 1961 I had about ten people. Now this did not include launch vehicles. As you recall, there was a separate arm, reporting directly to the associate administrator at the time, for launch vehicles. But it did include the whole Mercury program, Gemini, and the Apollo spacecraft, as well as the mission planning for Mercury, Gemini, and Apollo. Out of those 10 people, which included three or four secretaries, only one, John Disher, was spending almost full-time on future programs.

After Brainerd Holmes came on board, my responsibility became that of directing the spacecraft and the flight missions. I organized four separate elements, one of which was entirely for Apollo, under John Disher, and this became the largest element of the group. Other elements were on Mercury and Gemini, under Colonel Dan McKee, and he might have had two or three men on Mercury, but the rest of the people were working on Gemini. There was an Operations group, under Captain Van Ness, which was mostly involved with Mercury in that period of time. So during the summer of 1961, the fall of 1961, and leading into 1962, more and more of my group was devoting attention to Gemini and Apollo, but we kept essentially the same number of people we always had on Mercury, which was only two or three people in Headquarters. I would say I probably spent less and less of my own time on Mercury.

[335]

Interview #2

Do you recall the story behind the adding of the fifth engine to the Saturn V?

My recollection is Brainerd Holmes' first management council meeting, which would have been in December of 1961. It was also the first time that I met Joe Shea. I think Joe was just coming onboard and sat in on that meeting-and we were in Brainerd Holmes' office in the building at 19th and Pennsylvania. We had a model of the Saturn V. I don't know what it was called at the time but it had four engines on it. Von Braun and a number of us were standing around the table before we went into the meeting, looking at this model, and von Braun started saying, "Here is where we want to put the other engine." That's the first I remember hearing about it. I asked him, "Why do you want another engine?" and he replied that, "Well, there's this big hole that is just [336] crying for another engine." He did, in a very forceful way, say that this is a capability that this vehicle should have and we ought to put it in.

I remember my job at the time was to look out for the Bob Gilruth half of OMSF, and Milt Rosen looked out for the von Braun half at the time. I remember talking to Bob Gilruth on the side and asking him what he thought of the added complication of one more engine. I was probably negative to that kind of change, but I'm not even sure of that. Bob said, "Look, I'm so dedicated to LOR and if that will be the only way to go for that kind of approach I'm sure we'll be able to use the added weight-lifting capability if we have the fifth engine. So let's go ahead with it." I think even at that time-long before the LOR decision was final-Bob was convinced that this was the only way to go.

What about Max Faget and the LOR decision?

That goes back to the Low Committee days. And in that context, we assigned different things to different people-a small group or a small committee. I assigned Max [Faget] to go to Langley to talk to Houbolt and to come back with an assessment of LOR to see whether we should consider it further. Max came back and spent quite a bit of time at the blackboard proving that we should not consider it. And none of us were smart enough to question him on it. It was a mistake on our part, on my part, I guess, not to probe further and turn Max around. The course of events might have gone differently. Max turned around not too long thereafter, and I think Bob Gilruth probably helped turn him around . . .

Have I ever talked to you about Jim Chamberlain and LOR?

No, I don't believe you ever have.

Jim Chamberlain had grandiose ideas about Gemini. He wanted to skip Apollo and take Gemini to the Moon. He came to meet with Abe Silverstein and me sometime in late 1960 or early 1961, and sketched out how we could use Gemini to land on the Moon using LOR.

[337]

Regarding the crew selection process, do you know how that worked within the Astronaut Office?

On Mercury alone, I think Bob [Gilruth] started out with peer ratings. He asked each of the seven, "if you were unable to fly, assuming you wanted to fly first but were unable to, who would you like to see fly next? And why?" He used that information, and he asked Charlie Donlan and Walt Williams, both of whom were his deputies, for their input. And finally, based on all of that, he made his decision.

Gemini, Shea says, "was controlled completely by Slayton. Gilruth merely rubber-stamped." I think rubber-stamping is going too far. In the Apollo selections, when I was deputy director of the center [the Johnson Space Center], and even later when I was Apollo spacecraft program manager, Deke Slayton would come in with an overall plan and a detailed selection. He would say, "Here are the men I have that can fly; these are potential commanders; [338] so-and-so does not look like a commander to me but he would be a good back-up man; this man is very good at EVA, this man is particularly good at systems." He flew Gus Grissom first in Gemini and then again in Apollo because he thought so very highly of him, his engineering-pilot capabilities. He put all of these things together. And then Deke and Bob [Gilruth] and I would discuss Deke's plan at great length. Deke would discuss the overall plan and then say "now the guys I want to fly on the next selection-which probably was not the next mission-would be these and these would be the backup." The specific recommendations were based on the overall plan. I can't think of a single instance where Deke changed his mind based on our questions, or we changed Deke's mind. So if Shea wants to call it a rubber stamp, he may. I don't know of an instance where we disagreed with Deke's recommendations. But I would rather pay tribute to Deke's abilities in what he did than to say that no matter what Deke would have come in with, we would have accepted it.

I talked with Deke once about the only time he was overruled, and that wasn't by Gilruth, it was by Mueller, about putting Shepard on [Apollo] 14 instead of 13. The decision shows how lucky Alan Shepard was.

That's right.

He said he never knew why Mueller wanted that change made. Do you recall-

I was still in Houston. I remember Sam Phillips worrying a great deal about this one, and I remember Sam asking me on the side did I think Al should fly or not. I remember that Chris Kraft and I had many discussions about this. I think this was about the time of the Apollo 11 return . . . My concern about Al was whether a man who had taken command of a group of people and who really had not gotten his hands dirty for a while-had really been a leader of a team instead of a team member-would get back to work. Would he really knuckle down and take [339] instructions from the flight controllers? Would he listen to them? Would he do what they asked him to, or would he throw his weight around? Both Chris [Kraft] and I were concerned about that. Chris and I, I think, both privately talked to Al about it. I know we talked to Gilruth and Deke about it and convinced them and ourselves that Al really wanted to fly so badly that he would knuckle down and he'd probably be one of the most dedicated pilots we'd ever had. And I think as it turned out, it proved that this was the case.

Now, why was Mueller against flying him on 13? Now I have to speculate. George did not like to lose a battle, to lose any kind of an argument, to lose any kind of a fight. It could be that by postponing Al's flying by one flight at least made him not lose completely. He sort of had to give in to the overwhelming support that Al Shepard had for flying, probably including Sam Phillips' advice, but finally said, "but will he really be ready? Remember, he hasn't flown since Mercury, he has not been in detailed training. How much time do you normally take for training? Don't you need that extra time period to train him?" And probably the other side, Deke and company, gave in to that argument . . .

I was one of two people who told Al Shepard that he would never fly again. Many years earlier, Bob Gilruth and I met in Bob's office with Shepard after we talked to Chuck Berry in detail. Chuck had told us that Al had Meniere's Disease, that this was incurable, and that Al would never fly-should not fly again. Al had high hopes always, and never gave up. Bob and I sat down with Al and told him that he would never fly again and might as well face it . . .

I remember Bob had a yellow couch and Al was sitting in it and we were sitting on the two sides, and it was one of the most difficult things I have ever participated in because telling a guy that what he's wanted all his life he won't be able to do is very, very difficult. Al, on his own, made himself flyable again. And I think from every point of view, from the point of view of compassion for the man, from the point of view of letting an incurable, whatever the incurable is, achieve his goal after he has been cured and what this can mean to people around the world who consider themselves [340] incurable with more serious things, and knowing that Al would fly a good mission, I think there was just no question about it-that doesn't mean there weren't other people equally qualified or better qualified to fly-you put all of those things together and I think it was the right selection. I don't know what I'd be telling you if he'd blown it, but I don't think he would have.

Well, everybody likes to see a man come from behind like that. Especially one who was responsible for telling him about it.

Yes. And you know I didn't have all that much to do with selecting him at that time. I was off on the side making inputs so I can't take any credit for it. But I remember talking to Al and telling him the story after the flight. I said there's nothing that pleases me more than to have been so wrong-when I was one of two that told you you'd never fly again. It meant a great deal to him, and I think it was the right thing to do. I don't think NASA-or the people who selected the astronauts, including Deke Slayton or anybody else-needs to be ashamed for considering human beings when they make flight selections. As long as you don't select the wrong person. And I don't think that you have to select-what in a systems engineering, computer-run, paper organization would be-the ultimate best choice, because when you deal with people you can't . . .

I know of only one selection where if Deke had his own way, or for that matter probably JSC had its own way, it would not have been made, and that was with Jack Schmitt [Apollo 17]. I don't think Jack would have flown if it hadn't been pushed very hard from up here.

What about the capabilities of the spacecraft to land on land?

One of the things that I got into fairly quickly was that the spacecraft [Apollo] as designed did not have a land impact capability, that had been ruled out, and it was said "we aren't going to land on land." On the other hand, if you looked at the trajectory from the launch pad for some early aborts, unless you restricted yourself to only high offshore winds, there were 30 seconds or so of land impact capability.

[341] You may have heard in each launch that we had the call to the astronauts, "feet wet," which means that from that point on-this call was, say 15-20-25 seconds into the launch-we finally had overflown the line and any abort would make us land in the water . . . there may have been some exceptions. On almost every lunar flight-had we a mission rule which said you only launch when the wind is such, that you'll only have water landings, we never would have flown to the Moon. Because those conditions seldom exist. So we looked at the conditions at the Cape, the probability of a land impact, and decided that there was a high probability that we would have to launch under conditions when there could be a land impact. That was ruled out by a wave of the arm of Joe Shea's board. We looked at it, we undertook a very expensive program of proving, and deciding what had to be done to the spacecraft to make land impact possible.

I remember I called back all of the spacecraft that we had in museums at the time for the land drop tests. We went out to the Cape and measured the hardness of the soil when impacted by a spacecraft. We built a miniature Cape rig in Houston with sand that simulated the Cape. We tested it. We had some horrible pictures of those things. And we finally redesigned the amount of material underneath the spacecraft-between the spacecraft and inner shell. We redesigned the structure that held the hypergolic tanks. And we put different kinds of struts and foot restraints on the couches. In fact, we changed Wally Schirra's [Apollo 7] foot restraints three days before the flight. We also started a new wind-measuring technique at the Cape, and a computer program which would tell us exactly what we had and what the wind conditions were. And through all that we were able to launch under conditions where it never would have been possible if we ruled out a land landing.

Did you start this land-landing capability immediately after you took over from Shea?

I don't know. I remember one argument that I had with George Mueller was on this subject, because it was costly. I came in for one [342] of the management council meetings, and among other things reported on the program that I was undertaking. I sought to understand the land-landing problem and to help fix it. And George said, "Well, what if you find that you can't withstand a land landing?" Well, we did find out what we could do. We were able to beef it up slightly, and through that we were able to ultimately write mission rules that allowed us to be much more flexible in flying. If we hadn't done it, two things could have happened. One is that later on Chris Kraft and the flight crew people would have prevailed on us and said, "Look, we aren't going to launch, or we aren't going to let you launch unless you have a water impact." And if we looked at that, as I said, with all the other launch window constraints on the lunar launching, we might not have launched toward the Moon. Or, we would have all gotten together and said, "Look, we will take the calculated risk that we kill a guy if we do have an early abort and land on land."

Looking back on Apollo today, that would not have been a bad risk because we didn't have a single abort. You can say, look we didn't have to make that change because we never had an early abort and we never landed on land, and therefore it was an unnecessary change. So you can look at any side of this you want to. But in retrospect, I think what we would have done is to compromise a little bit each way, and we would have written some mission rules which would have severely restricted our launch window and we might not have landed on the Moon before the end of the decade.

What are the things that really made Apollo go under your leadership-that made it possible to do the program?

The Change Control Board (CCB) and how it worked and the fact that I turned the whole software program over to Chris Kraft.

Chris had the mission control center, which had its own software but I'm talking about the programming of the onboard computers-the work that MIT [Massachusetts Institute of Technology] did. Chris Kraft and I, one time together, went to MIT to look at this system. I confided to Chris that I could not [343] take on the added responsibility of making these work. It was just too big a job for me to also learn and understand the onboard computers as I'm working the rest of Apollo. I asked Chris if I could turn the whole job over to him. And I did, and he accepted it. The only thing I did with software thereafter is, once a week in my management center, meet with one of Chris' guys to review the schedules, make sure that the schedules were compatible with what we were doing. But Chris ran the Change Control Board. He worried all the changes, all the technical problems, all the astronaut interfaces, which were important and ran the show. It was just one problem. I gave away a third of Apollo to a guy that I knew could do it better than I could. And then I didn't worry about it anymore. And I'm frankly convinced that if I had kept it in my shop and had tried to do it, plus all the other things I was trying to learn and do, I couldn't have done it. So I started out defending CCB, but I think those two things together, the CCB and all the help I got from the Fagets and the Krafts and the Slaytons, and with Chris taking over the whole software package, were the two things that made Apollo possible.

ENDNOTES

1. After newly elected President Kennedy's victory over Richard Nixon in November 1960, Kennedy formed a "transition team" to assess the national space effort. That team was headed by Jerome B. Wiesner, a Massachusetts Institute of Technology physicist who would become Kennedy's science advisor. The "Wiesner Report" was released on January 10, 1961, and was highly critical of the quality and technical competence of NASA management, and of the heavy emphasis that had been placed on human spaceflight. It called the Mercury program "marginal" because of the limited power of its Atlas booster and criticized the priority given to the Mercury program for strengthening "the popular belief that man in space is the most important aim of our nonmilitary space effort." "Report to the President-Elect of the Ad Hoc Committee on Space," January 10, 1961, NASA Historical Reference Collection. Quotes are from p. 9 and p. 16.

2. In the spring of 1959, a Research Steering Committee on Manned Space Flight was formed and chaired by Harry J. Goett of NASA's Ames Research Center. The Goett committee considered NASA's goals, beyond the Mercury program and by the middle of 1959, concluded that the appropriate objective for NASA's post-Mercury human spaceflight program was to send humans to the Moon.

[344] 3. Mercury-Redstone 2 (MR2) was launched from Pad 5 at Cape Canaveral, Florida on January 31, 1961. The spacecraft carried a 37-lb chimpanzee named Ham, a name derived from Holloman Aerospace Medical Center at Holloman Air Force Base, New Mexico which is where the Mercury animal program was based. The purpose of the flight was to qualify the spacecraft for launch aborts by firing off the escape rocket which carried the spacecraft away from the Redstone. The 4,190-lb. Mercury spacecraft no. 5 was lobbed to a height of 157 miles at a maximum speed of 5,857 mph and a downrange distance of 422 miles in a flight that lasted 16 minutes and 39 seconds. Ham experienced a maximum acceleration of 14.7 g due to a large overthrust with the Redstone, which threw the spacecraft to a greater distance than planned. Because of this, a booster development flight, dubbed MR-BD, was flown on March 24, 1961, with spacecraft no. 3, reaching a height of 113.5 miles, a speed of 5,123 mph and a downrange distance of 307 miles, fully qualifying the Redstone for the first manned Mercury flight.

4. In an attempt to launch the first Mercury-Redstone on a preliminary suborbital test of the spacecraft and launch vehicle combination before a primate flight, NASA attempted to launch MR-1 on November 21, 1960. However, the Redstone motor prematurely cutoff when the launch vehicle was about one inch off the pad. It settled back to its pad supports, but since the spacecraft received a cutoff signal it triggered its launch escape system and recovery parachutes. The launch escape tower broke free leaving behind the spacecraft on the launch vehicle with parachutes draping over the top shortly after the recovery equipment deployed itself. A second launch attempt, dubbed MR-1A, successfully launched on December 19, 1960. The spacecraft reached an altitude of 131 miles, a speed of 4,909 mph and a downrange distance of 235 miles before being safely recovered from the Atlantic Ocean.