SP-4223 "Before This Decade Is Out..."

[60]

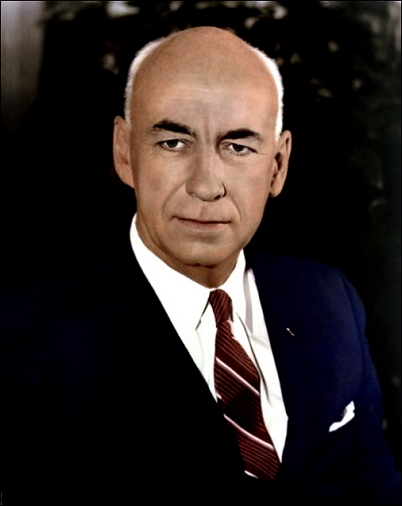

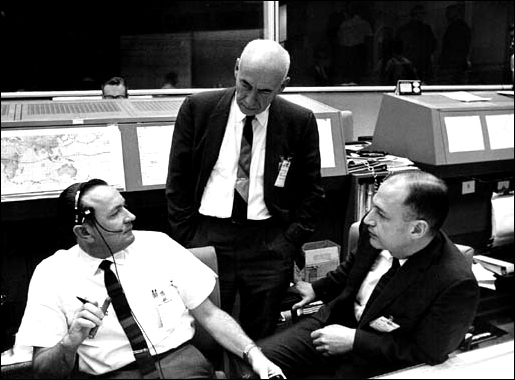

[61] Dr. Robert Rowe Gilruth's entire professional career has been devoted to government service, first with the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA) and then with its successor, NASA. In his early years, Dr. Gilruth was deeply involved in transonic aerodynamic research. He used free-falling instrumented bodies dropped from high altitudes, and the wing-flow technique he had invented, to solve problems of aerodynamics near and through the speed of sound.

Born on October 8, 1913, in Nashwauk, Minnesota, Dr. Gilruth received a bachelor of science degree in aeronautical engineering in 1935 from the University of Minnesota, followed by a master of science in aeronautical engineering in 1936.

In 1945, the United States Congress approved the establishment of a free-flight guided missile range to be built at Wallops Island, Virginia, and operated by NACA. Dr. Gilruth was selected to manage this new facility. Although he was a young man of 31 with little experience except research, he soon mastered this new world of budgets, land acquisition, recruiting, and operating with other government agencies and industry. Originally conceived as a missile test site, Wallops soon became a missile research range and Dr. Gilruth began developing basic information [62] on the aerodynamic and structural behavior of wings, bodies, controls, and other key items in missile and aircraft design.

In 1952, Dr. Gilruth was appointed assistant director of the Langley Laboratory when, during this period, he acquired a nucleus of people who were skillful and creative in research with rocket-powered models in free-flight at supersonic and transonic speeds. He directed research efforts in hypersonic aerodynamics at the Wallops Island Station and the research in high-temperature structures and dynamic loads at the Langley Laboratory. The results of Dr. Gilruth's research on the behavior of wings and controls at sonic speeds, and his analysis of wing flow tests on thin wing sections for aircraft designed to fly men through the speed of sound, were available in time to be considered in the very thin wing section for the X-1 research aircraft, the first aircraft to "break the sound barrier." Because of the Wallops Island research results, there were practically no surprises during this historic flight. When the X-15 aircraft, which had been proposed for flying men to the very edge of space and back, became a successful research aircraft,

Dr. Gilruth and his associates began thinking about manned satellites.

With the replacement of NACA with NASA in 1958, Dr. Gilruth became the director of the Space Task Group at Langley Field, Virginia, the organization responsible for the design, development, and flight opera-tions of Project Mercury, the nation's first manned space flight program. It was during this time that Dr. Gilruth helped organize the Manned Spacecraft Center (now the Johnson Space Center) in Houston, Texas, and selected a highly competent workforce capable of performing the many diverse functions required for a program of this magnitude.

Leading that effort, Dr. Gilruth became director of the Manned Spacecraft Center in 1961 where he served until January 1972 when he took on a new position within NASA as director of key personnel development. In this capacity, he was responsible for identifying near- and long-range potential candidates for key jobs in the agency and for creating plans and procedures that would aid in the development of these candidates.

In December 1973, Dr. Gilruth retired from NASA and, in January 1974, was appointed as a consultant to the administrator. In February of that same year, Dr. Gilruth was appointed to the Board of Directors of Bunker Ramo Corporation. He was also appointed a [63] member of the National Academy of Engineering (NAE) Aeronautics and Space Engineering Board (ASEB), and asked to serve as a member of the Houston Chamber of Commerce Energy Task Force.

During his long and distinguished civil service career, Dr. Gilruth has received many honors including being elected a member of the National Academy of Sciences and a member of the National Academy of Engineering. In 1972, he received the Robert J. Collier Trophy for the greatest achievement in aeronautics or astronautics. He is also an honorary fellow in the American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics; a fellow in the American Astronautical Society; an honorary fellow of the Royal Aeronautical Society; and a member of the International Academy of Astronautics. In addition, Dr. Gilruth served on numerous scientific advisory committees for the military services and NASA. Honorary degrees bestowed upon him include honorary degrees of doctor of science from the University of Minnesota, the Indiana Institute of Technology, and the George Washington University. He received an honorary degree of doctor of engineering from Michigan Technological University, and an honorary doctor of law degree from New Mexico State University.

[64] Editor's note: The following are edited excerpts from four separate interviews conducted with Robert R. Gilruth. Robert Sherrod conducted interview #1 on November 16, 1972. David DeVorkin and John Mauer conducted interview #2 on October 2, 1986. David DeVorkin and John Mauer conducted interview #3 on February 28, 1987. David DeVorkin and Martin Collins conducted interview #4 on March 2, 1987. The last three interviews were conducted as part of the Smithsonian Institute's National Air and Space Museum Glenn-Webb-Seamans Project for Research in Space History.1

Interview #1

The Soviets, having launched Sputnik, in a way, made putting a man into space worthwhile. You had doubts about it before, as to whether it was just a stunt or not, but this now gave it meaning. I don't want to put words into your mouth, and if I'm not saying it correctly, indicate what your opinion was at that time.

Let me tell you that to the best of my knowledge, I never thought of flying people in space before Sputnik. When Sputnik went up, it was a shock. And it was not just a shock to me, but it was a shock all the way through the technical people of the United States, including a man who was my "big boss" in Washington. By that time, Dr. George Lewis, who had been the head of NACA for many years and was responsible for all the wind tunnels, and Dr. Hugh Dryden, who was affiliated with the National Bureau of Standards, were working sort of free-lance at the time after Sputnik went up, trying to help the country get hold of itself and get a program that would do well. Sputnik went up on October 4, 1957, and on November 3 they put a second Sputnik up with a dog [named Laika] in it. On that second flight I said to myself and to my colleagues, "This means that the Soviets are going to fly a man in space." They've got so many accolades from all of the people all around the world. The Soviet stock, so to speak, went way up, and they began to emerge as the leading technical nation in the world.

So after the dog went up-that was on November 3- on November 7 President Dwight D. Eisenhower appointed Dr. James R. Killian as special assistant to the president for science and technology, which meant that even Eisenhower was affected [65] quite heavily by this. Then, on November 21, Dr. Dryden, who was filling in now for NACA, created a Space Technology Committee at NACA. He was, of course, on that Committee along with Dr. Wernher von Braun, Guy Stever-who was a member of many committees, a good man, and myself. Also, Jim Dempsey, who was head of the firm that was building the Atlas rocket, and Dr. Randolph Lovelace, who was the head of the Lovelace Institute, a doctor who was a very big help to us in our man-in-space programs. There were several other people as well. So there were quite rapid reactions to the fact that Sputnik went up. Jimmy Doolittle was also very instrumental along with Dryden in talking to the President mostly through the President's Science Advisory Committee. That was pretty much the situation. Early in 1958, the people at Langley worked on a space document for Headquarters that described the activities that we already had going in the space field which showed that NACA was active in this area.

Was it on November 5, 1958, that the Space Task Group, originally called the Task Group, was actually officially formed?

Yes. I saw that date somewhere. We called ourselves the Space Task Group before anybody knew why we did it.

Do you remember where the term "Space Task Group" came from?

I think it was the best thing I could think of. A lot of people wanted to call it the Task Force. I didn't think that was a good thing, Task Force. It was a group.

Not a Tiger Team?

Not a Tiger Team, not a Skunk Works. It wasn't any of those things; it was a Task Group.

I'd like to get at just that question, following that up. Why is group better than force for you?

[66] Because force is an adjective that implies you have a lot of strength. I didn't know whether we had a lot of strength or not.

Some people, when they build, try to appear as if they have the strength, hoping that this will make a lot of people assume they have it. They basically assume the position, and what they expect. Others build from the inside.

We had the strength. We had the money. What we needed was a good name, and we didn't want to sound like we thought we were too big for our britches. We were a Task Group. We had a big task and we were a group. It was a very good name. I wouldn't have changed it for Task Force. A Task Force is something you use in the military.

Interview #2

Let's talk a little bit about the first few months, the first year of the transition [from NACA to NASA]. I'd like to know-as you were asked to be on these task forces-were you given any kind of a choice and did you consider any different moves? All of Langley apparently was being absorbed, and I guess you knew that. Is that correct?

No. No, Langley wasn't. I was pried out of Langley and I started the Space Task Group. And I was sent back to Langley. I wrote to my friend, Tommy [Floyd L.] Thompson [director of the Langley Research Center], and said "I've been authorized by the administrator to draw out certain people from your staff and these are the ones I'd like." I listed a page and a half of key people that I wanted, and he let me have everyone except one. That was when one of his division chiefs said, "Bob [Gilruth] doesn't really need that one, we'll give you somebody else," but that one I really needed because he was doing a special job for me.

[67] But did you have the feeling that you were being pulled out of something that you would prefer doing? Was this something that you had to think twice about?

I didn't think I wanted to do this space business all my life, but I was fascinated by it. I thought it was terribly dangerous and probably I'd end up in jail or something, but I really thought it was important to do and I was having a lot of fun.

So you didn't resist it and you didn't see this as a dangerous move in your career?

I thought it was probably a high-risk move. If I failed, I knew that would be very bad. On the other hand, if it worked maybe that would be good.

Did you know what was expected of you?

Yes, I was expected to put man in space and bring him back in good shape-and do it before the Soviets, which we didn't do. On the other hand, we buried the Soviets before we were through by going to the Moon.

Was there a sense of failure because the Soviets constantly-in the initial few years-were ahead?

No, because we had no chance of overcoming them that fast. They didn't even say they had a program to put man in space. They never admitted they had a program to put man in space until they put the gear in space.

But you knew once Laika went up?

Once Laika . . . I said they've got to be doing it, sure.

One of my questions was, in reading [an earlier interview] where you talk a lot about the popular media's conception of the effect of [68] Sputnik, that it was a terrible surprise, that we were behind, that this was a threat to national security. You seem to think that it wasn't so much a threat until you realized what they could really do with some of the later Sputniks; Sputnik I didn't impress you that much. But, I'm wondering, did you see it as a threat or as a real opportunity to go from having, in the early mode of activity, a plan without a program, to a real program?

I think that as this thing unfolded, it wasn't going to be just one flight of man as the whole program. And that's why when Kennedy came along and said, "Look, I want to be first. Now do something." I said, "Well, you've got to pick a job that's so difficult, that it's new, that they'll have to start from scratch. They just can't take their old rocket and put another gimmick on it and do something we can't do. It's got to be something that requires a great big rocket, like going to the Moon. Going to the Moon will take new rockets, new technology, and if you want to do that, I think our country could probably win because we'd both have to start from scratch."

I usually heard this kind of logic attributed to von Braun. Is that correct? Or were there many people who had that logic?

Well, I think Wernher had that, too, but I was the one who was talking to Kennedy.

You were talking to him personally?

Yes . . . I was talking to him. And I told him that very thing. If you really want to be first, you've got to take something that is so difficult we'll both have to start from scratch.

You're speaking of Kennedy . . . Did you feel that you had a real program, or was it still a career risk for you during the Glennan years?

Well, I was not really happy with Glennan and I wasn't very happy with Eisenhower, because Eisenhower obviously didn't believe in the program. He'd been talked into it and he was reluctant. You know, he [69] took money away from the program in the last few months of his term. I'd seen Eisenhower, but I never met him or talked to him about it.

But you did meet Kennedy?

I saw Kennedy many times.

You state very clearly that the strength of the NACA was in the centers. And now you're moving into an area where there was going to be contracting. NASA was going to be a contracting organization, but it was going to bring in the NACA centers, it was going to be built on the NACA. Were you worried?

What do you mean, "built on the NACA?"

NASA in its early design was to be based upon the NACA centers. Is that a fair statement? Langley was going to be brought in, Ames, Lewis . . .

Yes, they were all going to be part of NASA.

Previously, there had been research centers either responding or dreaming up new research. Dryden had said or had hoped that NASA would retain these centers, these old NACA Centers, as research centers. Were you in fear that they would be changed from being pure research centers to becoming simply centers for contracting work out? A few minutes ago we said that you couldn't produce a new center that could put a man on the Moon. You had the contract with industry and you became literally a contracting agency. Were you worried that the vitality, the research vitality of the centers would be affected?

The way it worked . . .Langley, which was a research center, was very proud of the fact that it was a research center, and they did not want to become a contracting center. We who had a job of putting a man in space knew damn well that we had the luxury of having a few good men in a few laboratories that we could do some work in [70] support of our programs, so we would not be entirely dependent on the other research centers. And because we always like to have people who liked to do that kind of work, just to talk to . . .

You had to remain technically vital.

Yes. And so when we built our center-thanks to Mr. Kennedy and the Moon program-we were sent down to Houston where we built a center. Believe me, we built it from scratch. There was nothing there but a field with some cows on it.

But you didn't know this until Kennedy came in.

That's right. We were responding to a challenge of the country. We weren't sure what was going to happen. We thought we could do that job and if it turned out to be a dead-end job, the fact that we'd been able to do it, we felt, would allow us to do jobs elsewhere. I don't think we had a very big risk except of not being able to pull it off. That was a big risk.

Interview #3

In August 1959, you created what was called the New Projects Panel to identify new areas for research. I'm interested in how it was set up. You made [Kurt] Strauss the head.

Yes, Kurt Strauss. Bob Piland worked on that, too . . . We came up with this. We thought we ought to be looking ahead at what kind of a spacecraft we were looking at next? We came up with a place where you could do work, where you could do tests of weightlessness. We came up with a bigger capsule than Mercury, along with a tank-like object in which you had room to do experiments. That was really the forerunner of the lunar module. We worked hard on this thing, then when we came along with the lunar program, we were able to modify some of this and add parts to it. We actually saved a little time by having been looking ahead at some of these things.

[71]

When did you start thinking that there was going to be a center for manned spacecraft?

It became obvious. Mercury was a dead-end program. You were going to fly man in space, orbit him-that was it. I was ready to go back and sail my boat after that. Anyway, it didn't work out that way. We ended up with Kennedy and going to the Moon. That was a big program. There was no question that it couldn't be handled out of Langley, and it couldn't have been handled out of Washington. It [72] had to be handled out of Texas, because that's where the head of the Appropriations Committee lived. Right smack there in Houston.

So the Mercury program itself didn't warrant thinking really big?

That's right. It was a dead-end program.

You were aware of that right along?

It seemed to me that it was because you never stop with the one thing you're doing. But it wasn't obvious what the next step was.

What was it about your experiences that let you have confidence in getting into this whole new area of dealing with contracts?

I didn't have time to think about that problem. It seemed to be very straightforward. The people at McDonnell, I'd known before. I knew Mr. McDonnell and [John F.] Yardley, a stress analysis man who late became president.

So you already knew many of the key contractors?

I knew them. But I'd never had a relationship where they were the contractors. I was "Bob" and we could talk about what the problems were. We really didn't have any bad problems. We had arguments about how the capsule should be built. And we resolved those on a rational basis, and I think we were satisfied. It wasn't hard to do that. The Atlas was a little different because we were buying it from General Dynamics through the Air Force. Of course the Air Force was really quite concerned that we might give their rocket a bad name because they weren't sure that we knew what we were doing. And especially when we-the second Atlas we flew blew up at Mach 1 just 60 seconds after it was started, and-

But that was prepared by the Air Force for you, wasn't it?

Yes. But see, it was a case of, we had our spacecraft on the front, [73] and they said, "Well, that came apart and went back and hit the Atlas and caused it to blow." Which it might have.

They also had motivation to blame your spacecraft, because if they blamed your spacecraft, then their rocket wasn't to blame.

Sure. And obviously, there was a case for an argument, and we wanted to fly again. And I said, "I believe that the skin of your rocket is too thin," I think it was 20/1000th. The Atlas was a stainless steel balloon. I said, "The turbulence from our spacecraft is probably enough to cause that to oscillate and wrinkle and it probably ruptures." So I wanted to put a collar around it of heavier stainless steel with bands that would tighten it up, and I made the mistake of calling it a "belly band." This was very, very unpopular with the Air Force. But I said, "We paid for this rocket, and we need to fly." They said, "Well, we'll put heavier gauge material on the rocket, but that will take five months to do." I'd already looked into that, and I said, "We can't wait five months. We need to put the belly band on." Nobody in the Air Force would approve it. We finally carried it all the way to the Secretary of the Air Force, who I'd known. I said, "I will agree to take all blame if it breaks," which meant I would be out of a job. I said I was the guy that insisted on doing this-I said, "okay, I'll take the blame if it blows." Well, we put the belly band on, and I remember very well when we launched that thing. I went outside all by myself, behind a bush there, and watched that thing go. I kept timing it, and when 60 seconds elapsed, that was the time it went through Mach 1. It kept staying together. Then I went back into the blockhouse and I said, "Well, we can relax a little bit. We didn't have that problem again." That saved us four or five months in our program.

You came up with the idea, or someone on your staff, and took responsibility for it, the belly band?

The belly band? Oh, I don't know. I think maybe it was somebody like Yardley who said, "Well, what we need to do is to strengthen [74] that up," and so we got the idea of the belly band. But it was my idea to carry the thing through the hard knocks.

You never asked somebody at Headquarters to vouch for you?

Well, Jim Webb was head of NASA and he knew all about it. I told him. He knew our problem.

But you were the one who was ready to take the heat.

Yes, somebody had to take the heat and I was the logical one. And maybe he [Jim Webb] would have saved my neck, if it had blown up, but I don't think he could have. In any case, that's a true story. That was really an important thing, because we couldn't have stood that four or five month delay.

Let me ask, why did you leave the bunker? Why did you go outside to watch it?

Because I wanted to get the best possible view of what was happening. Inside, you couldn't see very much. You could see all the instruments and everything.

But it sounds like, having put your job on the line, you were also willing to put your life on the line.

Oh, no, no. It wasn't dangerous.

It wasn't, even at launch?

I wasn't that close to it.

In listening to your account, it strikes me differently, maybe it's in the record and I just didn't pick up on it before-but the failure that prompted you to come to the belly band decision, was it directly associated with the dynamic forces of going through the sound barrier at Mach 1?

And is that why you went outside, because you wanted to see the rocket's actual performance when it went through the sound barrier?

Well, you could see the failure better from outside than you could on a television screen inside.

If that problem was going to be repeated was it going to be repeated at Mach 1?

Yes. That's where it happened before, and that's where the buffeting was the worst. If you got through that, I thought we were perfectly all right. It turned out that it was. From then on, we had three good Atlases in a row. No, four. I think every one. Glenn and all the other astronauts except Grissom and Shepard flew on that Atlas-Deke Slayton, of course, didn't fly.

Did they fly Atlases with belly bands?

No, from then on they had the thick skin.

So the belly band was a temporary thing to bridge between the very thin one to the new one.

That's all it was, so you could make your flight without losing five months.

Did you ever have a feeling, during the Mercury Program, that without rules in the beginning, without an adequate infrastructure to monitor the contracts and all of the different phases of Mercury, especially at the point where you were also beginning to worry about building a new center, that things might get out of hand? Did you have contingencies, fallback positions?

I don't think that we felt particularly bad off in our monitoring of the Mercury spacecraft, for example. Or the Atlas rockets, because [76] we were just buying those Atlas rockets, and we had one or two men there to investigate-when we were worried about the pumps. We routinely took the pumps apart to check the clearances in them, which was not a regular procedure.

But you did do that.

We did that. We had three or four good Atlases in a row, which is more than they usually got. And we didn't have very many people for some of those contracts. The price was already set by the Air Force. We just bought it through the Air Force.

So in a way, Mercury is different because you're just focussing upon specific parts of the program. Other parts, you're just buying in to what already was being developed.

That's right. There were some changes that were made. We wanted a different skin gauge on the front end of the Atlas. We had another rocket that we used, the Redstone, for suborbital flights. We were able to get them from von Braun and his people, and they were glad to be with us. They were a big help to us. We also had one of our own rockets. We had a solid rocket launcher that we used at Wallops Island to test some of the spacecraft. It was just a great big solid-

Little Joe?

Little Joe. And we used that for some of the escape system tests to save money.

In a way it's an advantage to buy a technology that's coming onto line because you don't have to worry about shepherding it through. On the other hand you're buying a technology that's blowing up on the pad a lot. And you're wanting to put a man on top of that-

That's right.

[77] Did it make you nervous when you thought, we don't have control over the Atlas. We're buying what already exists. To some degree it did, but you give the example about checking the tolerances on the pumps.

There were some things we could do, and that was one of them-the tolerances on the pumps. We did increase the skin gauge. But the Atlas was an Atlas, and we knew that we were going to have to live with what existed.

Why did you feel that you could live with it? What was it about the Atlas that made you feel, this can work, even though there are some problems?

We had no alternative. We had to. And we did. We only had one Atlas blow. That was the first. We used an Atlas on Big Joe, and that was in the first year of our program. We sent a Mercury, made in our own shop, a Mercury capsule shape that we used to measure the heat transfer and stability. We sent that up and drove it back down into the atmosphere. It was a marvelous test. It showed that the spacecraft was stable, that the heat transfer was what we thought it would be, and that a man could survive. Since we couldn't find the capsule right away, the papers all went to press and said it was another bust in the space program. The Navy found the capsule in a couple of hours and it was in good condition. The newspapers wouldn't publish the fact that it was found . . .

It must have been a very poignant time. How serious was, to you personally, press attention, and how adequate was it in general in those first years?

Our first year it was a strange situation. The Air Force ran the missile range down at the Banana River [Florida]. The headman was kind of like a little Napoleon. He was the boss and right after every launch he'd call all the press in. He'd get the people who had made the flight to stand up and say how it worked. In our case we didn't know how it worked because we were recovering something that [78] was way down range. It wasn't just whether it blew up or not within your view. We couldn't have a good meeting because we didn't know how it worked. We hadn't yet recovered it. So the press went with the fact that it was lost . . .

In that situation, five months was at a premium because of the intensity of the race with the Soviets.

At that time, Gagarin hadn't flown yet. We were still hoping that we could somehow or other luck out and orbit a man first, but Gagarin flew right before we flew Al Shepard. The Wiesner Committee held us up-otherwise, at least, we could have-

The Wiesner Committee held you up?

Sure.

In what respect? I don't remember that part of the story.

When the Republicans lost and Kennedy took over, the Science Advisor became Jerry Wiesner of MIT, and he was very much against the man-in-space program, and Kennedy had no polarity at all. He didn't know much about it and was not interested. So Wiesner decided to hold hearings on the man-in-space program, with the idea that it should be stopped. But Jim Webb had also been picked by the Republicans. Jim Webb and I had fortunately gotten to know each other, and he thought that we had a good thing going. He wasn't supposed to administrate a program that lost all of its guts, so he was my friend. When Wiesner had these hearings to see whether or not Mercury should be cancelled-

This was in January of 1961 . . . early 1961, right after Kennedy became President?

Yes.

And [T. Keith] Glennan was-

[79]

Glennan was no longer the Administrator of NASA.

That's right.

Webb was the new man running NASA. So the Wiesner Committee had some doctors on board who would not believe that man could stand weightlessness even for a few seconds. I said, "Well, we can take you up in an airplane and fly weightless, and it doesn't do anything bad to you. It hasn't hurt the monkeys that we orbited. We've already done that." Of course, we were going to make ballistic flights, up and down, like Al Shepard's flight. We hadn't made that yet. And we were trying to get permission to make the Al Shepard flight, and we couldn't get permission from Wiesner that it was safe, not from the point of view of the rocket blowing up, but from a point of view of, was it [80] worth it and could you stand weightlessness? This went on for quite a while, and finally Webb got frustrated, and said that we're going to go ahead and fly. We believe that we've done everything we can do. We have this program and we're going to fly, and if you don't think that's right, you will have to make your case in the newspapers.

This is Webb talking to Wiesner?

I don't think he talked directly to Wiesner, but he gave him that message. And so that's the way it ended. We went ahead and flew Al Shepard, and when Kennedy saw how the American people loved that flight, it was all over as far as Wiesner was concerned.

Interview #3

Some people are nostalgic for that Mercury period, because of it being so much freer, people making a lot of decisions quickly. How do you feel? How does it compare to the time before, and how does it compare to after you were already at the Manned Spacecraft Center? Does it seem to be a better time or is it just another stage in your career? How do you view it?

I don't think you could live through many of these Mercury programs. It was something you do when you're young. You couldn't keep on doing that kind of thing. It was a case of working all the time, for the first year or so. But it was rewarding. It was great when Al Shepard flew, and when Glenn, and all the others flew-we were extremely fortunate to have all those things work.

It was the fact that it was so very successful, I believe, that we went on to the lunar program. Although it is true that Kennedy really got that going before we ever orbited John Glenn. I think the momentum of those Mercury flights had a lot to do with the success of the Apollo Program over those years, because it made it a lot easier to get the money that it took. It took a lot more money to build Apollo than it did Mercury. Apollo was $20 to $30 billion, [81] and Mercury was, I think, closed out finally at about $400 million. We didn't think it would cost that much, but it did.

Interview #4

Why don't we go ahead and discuss the building of the Manned Spacecraft Center, later named the Johnson Space Center, in Houston, Texas. This was all part of the first year of decision, as you've described it, June 1961 through June 1962, when a center was found to be necessary.

Yes.

Where do we begin? I think we could use your advice on this. You were worrying about a hundred things at once. By then you had three major programs to concern yourself with: Mercury, which was operational, Gemini, and Apollo. You had manpower problems in simply determining who was going to work on which projects, where people could best be assigned, bringing new people in, worrying about everything from launch site to the goals and missions of the government, to the type of orbit, launch vehicles, test and operations, astronaut selection and training, orbit analysis, to celestial mechanics, just to name a few.

Yes. On top of that, we had to move.

But you didn't have to move.

Oh, yes we did.

Why?

In order to get the political backing we needed.

Okay, but you were in a program that was a hallmark of efficiency and directness and supposedly an absolute crash program to be [82] done as efficiently as possible. What sense did it make to you at the time, and to the people you worked with who were going to be affected, moving from Langley to anywhere else? Didn't it make more sense to stay?

Yes, it did make more sense to stay. But I can quote you how Mr. [James] Webb handled that. He said, "We've got to get the power. We've got to get the money, or we can't do this program. And we've got to do it. And the first thing," he said, "we've got to move to Texas. Texas is a good place for you to operate. It's in the center of the country. You're on salt water. It happens also to be the home of the man who is the controller of the money." That was Albert Thomas.2 So we moved. It turned out that it wasn't all that bad. We would have had to expand like hell anyway. When we went to Houston, we went into temporary buildings, which we would have had to do at Langley or at Hampton or at Newport News or somewhere. And it wasn't as good a place to live. The people weren't as gung-ho in Virginia as they were in Texas. They wanted us in Texas. They were thrilled to have the space program come to Texas.

Let's talk a bit about what he did do, and that is, take a person like John F. Parsons [associate director of the Ames Research Center] and send him out to do an open site survey of 10 possible sites in the United States, for where the Manned Spacecraft Center might be. Was this a necessary thing to do politically, or just a sham?

I think it was good to know what the reception would be in other parts of the country and what the advantages were. Actually, looking in retrospect at all the different places that were surveyed, I think they picked the best place.

Had you been there during the summer?

Yes, but it's not too nice in a lot of other places during different times of the year.

[83] Some of the people that came down from Langley initially ended up going back to Langley, just because they found the jump too much. But for you personally, you didn't feel like the jump was that big a deal, in terms of the climate, the situation?

No. I thought it was a lousy climate. But the air conditioning was good, and the people were nice, and it had other things. The winters were quite good compared to what we have here in Virginia. So it wasn't all bad.

Many people have the assumption, so I would like to address it from that point of view, that it was Lyndon Baines Johnson who was one of the key driving forces for the selection of Texas and Houston. You are pointing to Albert Thomas as being much more the important political influence. But how much of a role was the fact that LBJ was from Texas?

I think he was important also. But I think Albert Thomas was more powerful.

It's the difference between being chair of the key committee in the House and being vice president. You're not that powerful when you're vice president.

LBJ was very anxious to have Texas get that, too. But I don't know. I was just the innocent person there. We went down and looked at Houston. Webb said, "Why don't you go down there and look?" I looked around, and I was happy to see there was salt water, and there was lots of open space. Around Clear Lake it was fine. We looked at where we could build the center, and there were cows munching on the grass. I still have a picture of that site, with cows roaming on it. When I go back and look at that center now, I'm very proud of what was done. It's beautiful and it's been very valuable to the United States. So I feel that maybe Albert Thomas had a different motive, but it worked out to be in the interest of the United States of America.

[84]

Since there was a difference in the management approaches of [T. Keith] Glennan and [James] Webb, how did [Hugh] Dryden's role change between the time of working with Glennan from working with Webb?

I don't think his role changed much. He was the technical center. He was the last resort on any real problem that was technical. Neither Glennan nor Webb would try to vie with his knowledge of technology and science. It made a very good combination.

How did the strength that Dryden provided, in terms of his technical knowledge and his ability to give administrative leadership, change after he was no longer with NASA? Did it make any differences for you as a center director?

[85] There really wasn't any way of replacing Dryden. Dryden was a big loss. Of course, it was near the end there. I can't remember exactly when Hugh died.

It was 1965, I believe.

It's before we landed on the Moon. He had cancer and he would get treatments. When he'd get a treatment he'd be feeling good for a while. Then after two or three weeks he'd begin to drag, and finally he'd go in for another treatment and then he'd feel good. But he said, "You know, this recurrence will not go on forever, and each time it's a little worse." He knew it was inevitable. A very brave wonderful man, highly religious man. I can remember it was during Gemini that he passed away. It was the first time I ever left mission control during a manned mission, when I went to his funeral. God bless him. We sure missed him. But we forged ahead and did the best we could.

Interview #1

I mentioned to you . . . a visit the astronauts made to the [LBJ] Ranch in April of '62 . . . I asked President Johnson about that and all he said was, "They came over to air their grievances." Do you recall what the grievances were?

As I recall that trip to the ranch, it kind of got started . . . I don't know whether you remember that period. That was a period when everybody was trying to give things to the astronauts. A fellow down in Houston by the name of Sharp . . . wanted to give each astronaut a house. This was pretty confusing to those guys, because there's nothing wrong with having people give you something except what other people think of it . . .To a lot of people in this country, a house represents almost their entire ability to save all their lives. When they're old, they can finally own their own house. When somebody turns around and gives one away, why, they feel resentful about it. Well, some of the astronauts thought....

[86]

.....they ought to be allowed to accept those houses and it was quite controversial. And this was right around the time when, you remember, Deke Slayton was not allowed to fly because some of the doctors in the Air Force, who had gotten on the inside of our selection business, decided that they ought to serve their country by pulling the string on Deke, although they initially gave us assurance that he shouldn't be the first man to fly [in space], but they saw nothing wrong with his flying. And, of course, that's the right answer. There's no reason why he should've been prevented from flying. I fought for him all the time, but I couldn't fight against the M.D.'s when they got together and said it's not the thing to do. So, there was that problem, and at the Gridiron dinner one year when Kennedy was President-I was there and Al Shepard and I think most all the other astronauts, I know Deke was there, too-the President was brought into this. I guess they were a little upset, and the President was interested . . .

[87] But it wasn't publicly discussed.

Oh, no. No, certainly not.

Oh, I see. That's where the President learned about their grievances, in other words.

Well, this was one of the places. The way I remember it . . . the President had asked him [Lyndon B. Johnson] to invite the astronauts to come out to the ranch and kind of let down their hair and talk about things. And he asked me if I'd mind coming along with them. So I told him, no, I wouldn't mind coming along. We were there over my silver wedding anniversary, but I wasn't in a position not to go. So I went out there with them and we spent a couple of nights and a day.

That was a long session, then, wasn't it?

Well, we didn't spend all the time talking. We went around and looked at all the Johnson City things and the various parts of his ranch and his cattle and picked bluebonnets . . . Well, we did manage to have a couple of pretty good sessions about this stuff. And I think it was a good thing to do. This was right at the time that I told Wally Schirra he was going to fly the flight that followed Carpenter's flight. No, that Deke would have had the Carpenter flight. That's right. Deke would have had the second flight. Might have been Deke's.

Well, he had been assigned, hadn't he? Hadn't he been assigned to . . .

Yes, I think he'd been assigned. And then this thing came up and we put Carpenter in his place. And then Wally wasn't sure where he stood . . . So that's how it all happened. And these various points were covered and Mr. Johnson was very helpful, in helping those boys come to a concurrence that they shouldn't participate in some of this stuff. But I think most of them made up their minds . . . But it's nice to have top management take that much interest . . .

[88] There were a lot of other things, too, that I thought were not as questionable. Some of them invested their money in things like motels. And there's nothing wrong with that as long as they don't use their names and the fact that they own the motel. They ought to be able to invest their money in legitimate ways, the way other people do. You know, those guys have some rights, too. I think some of them went in with motels. I think the rules were clarified under which they ought to operate those things. So, it wasn't all the Sharp's thing, but there were a number of other things at that time that we talked about.

I can remember as late as '67, down at the Cape, if the word got around that an astronaut was in one of the bars, the bar would fill up almost immediately. Word of mouth would pass around, you know, they were still in there. And it was even truer, of course, in '62 than it was in '67.

Oh yes, that was wild down there.

. . .Nobody foresaw how instant fame would accrue to the astronauts the way it did.

Shorty Powers predicted it. I think that kind of guy would know the public mind pretty well, and he predicted it. I remember when he first told the astronauts what their lives were going to be like: that after the flight, after they've been debriefed, the first thing was they'd go to see the President. (And that was pretty damn true.) And that they'd probably appear before Congress and there'd be parades. That's the kind of ballgame we were in back in those early days of space. Of course, we saw it happen in the Soviet Union before we saw it happen in America. I remember seeing the pictures of Gagarin walking along that red carpet that extended about two miles from the airplane to the platform where all the party leaders were. And so they really showed us what the thing was going to be like before we started.

But it was pretty wild in those days when Al first flew and when he went to the Capitol. Webb and I went with him. I'll never....

[89]

Dr. Gilruth with his mother and father, Mr. and Mrs. Henry

A. Gilruth (left) and his wife, Jean, are shown on the White House lawn shortly

after receiving the "President's Award for Distinguished Federal Civilian

Service" from President Kennedy on August 7, 1962. (NASA Photo S-62-04851.)

....forget some of those experiences-going up there with John Glenn. And going to New York. I went to New York with John. Webb said, "Look, you're going to go right along with him and you're going to get every medal that he gets." And this was old Jim Webb, you know. He had in his mind that the astronaut thing was great, but the technical side was great, too. Well, he forgot one thing: in the eyes of the people, the thing that really counts is the guy who puts his life on the line. And they aren't so far wrong on that either. But Jim Webb did a lot to try to see that the astronauts weren't the only people in the whole show. I'll never forget some of those experiences. Some of them I had with Jim Webb himself. I saw him get the Medal of Honor that the City of New York gave him . . . It did my heart good because nobody could have done that lunar project without him.

[90] I remember in the last two or three months of the Johnson Administration, Webb was getting a medal every time he went to the White House. I said to him, "What is he trying to do, make a medal-of-the-month for you?" Well, you know, he got the civilian meritorious medal, or whatever the highest medal the President can give to a civilian.

Medal of Freedom.

Medal of Freedom. He really had tears over that one, because he hadn't expected it. Speaking of fame that accrued to the astronauts and such, what are your views on this stamp deal, the Apollo 15 mess that they got into, which opened up a Pandora's box of a lot of other little items from the past . . . Tell me about how these boys got into such a mess.

I don't know. I really couldn't tell you. I remember telling the crews when we brought them on board-I don't remember which set it was, it wasn't the original ones, it was the ones downstream of that, after I'd some experience-that if there's anything in your past that won't stand the light of day, right now you ought to resign, because it'll come up. There's no way it won't come up, because that's the kind of a ballgame you're in, you're a public figure, just like you're running for president. Furthermore, anything you do in the future, you ought to consider that you do it right on the street in front of all the people in the world in broad daylight. Because if you do anything that isn't completely right, it'll be found out and you'll be in trouble. Some of them might have listened to me, and some of them might have forgotten that. But that's the kind of way they have to live. Unfortunately, most people, if they do some little thing that's wrong, often they're caught and reprimanded without having it come to the attention of everybody in the world. Unfortunately, in the case of the boys in Apollo 15, they did something that, although I wouldn't say it was a crime, it wasn't exactly the right thing to do. And they didn't have any warning, it just went right straight out, and they were judged by it. Everybody in the world heard about it. So, I just feel that it's very unfortunate.

[91]

It certainly was a lack of good judgment that did it. And I feel very sorry for these boys, because it's awful tough on them, it's probably far more severe than they deserve for what they actually did that was wrong. But you can't blame it on anything other than just being naive, and probably talked themselves into the fact that, well, we're really doing a great thing, and we ought to get a little something for it. You know how you can talk yourself into something like that sometimes. I don't know, I've never discussed this with them, but this is what I think.

You never talked to the Apollo 15 crew afterwards?

I haven't had the guts to talk to them about it. Enough people have talked to them. The Senate has talked to them, and there are enough people that talk to them, and I just feel too sick about it.

[92] Well, of course, you didn't have to because you were no longer the director when this all broke.

I was no longer in the loop, in that sense.

I think I mentioned the other day that the only time that you, Deke, and others had been overruled on assignments of crews, was on Apollo 13 when Alan Shepard was taken off, I believe. Later he was put onto 14.

I guess you're right.

And Deke was the one who told me that George Mueller was the one who forced the change. How did he do that? Did he just telephone you in Houston and say you have to take Shepard off this?

I think it happened in Houston. I'm not real sure about that right now, but I remember Mueller coming and changing some of that in a way that we really couldn't argue against.

I believe his argument was that he hadn't had enough reindoctrination to fly that early.

Yes, that could well be. And it could have been that he was right, because we didn't put up any fight against it. But I think that probably was after 12. What kind of spacing were we flying at in those days? Was it six months?

Yes, 12 was in November of '69 and 13 was in April of '70. So that was just about six months.

I don't know whether we'd already announced crews.

No, you hadn't announced yet.

It was probably at the time we were debriefing the 12 crew there at the lunar receiving lab.

[93]

It must have been, because Mueller retired shortly thereafter. I think his retirement was announced within a month after 12 flew.

That was '69.

Yes, so it would have been sometime during that month's interval.

Unless it occurred before that. It could have occurred before 12.

Oh, of course. Thirteen would have been announced before then.

It had to be when we were debriefing after 11, because we had to have [94] more lead-time. I remember being there, of course, with Deke, and he kind of opened the whole gamut up. And our relations weren't awfully good with Mueller at that point. That was around the same time that we took on all the MOL [Manned Orbiting Laboratory] astronauts. And we knew we didn't have flights for all those people, and we told Mueller that, but he still wanted to take them on . . .

I was convinced that Al Shepard would make a very good commander for our mission. I'm very happy to say that he did an excellent job. I'm very proud that the first guy we had in space also was the guy that was able to lead an expedition to the Moon. It was great.

. . . Do you remember on September 17, 1962, you made a speech at the National Press Club3 in which you said that you trembled at the thought of the integration problems involved in joint missions with the Russians? And three days later President Kennedy came out with his proposal at the United Nations4 to . . .

Yes, I remember that. And I didn't know what the President was planning . . .

No, nor did anybody else.

. . . and neither did [Hugh] Dryden, who was right there with me at the time, and he sort of agreed with me. Well, I just said what I thought. I still think I was right. We were having enough problems trying to integrate Marshall and MSC at that time.

Well, now, you've been to Moscow on these recent deals. Does it look pretty good to you for integration of the whole thing?5

Yes.

Of course, the atmosphere is completely different from what it was in 1962 and 1963.

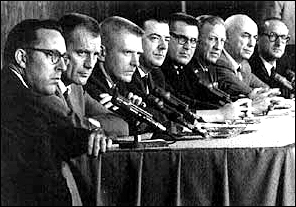

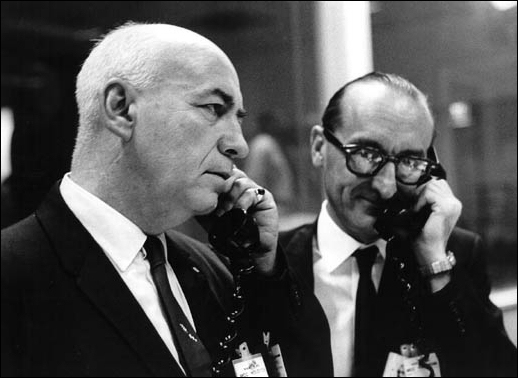

Well, actually, I led the first two groups over there. I went over there in October l970,6 and I guess that's the first time I really thought that we...

[95]

...might do it, because of the way they responded. I was told that, gee, that system is an impossible thing. We went over there and I didn't find it was impossible at all. I found the people to be very bright, and that the problems of talking back and forth through interpreters wasn't as tough as I thought it would be. They had an idea of how it could be done and they gave as much as we did. I met Keldysh7 and he was very interested in it. And he took us all out to dinner. I spent a couple of hours with him in his office talking about all this. And he spoke in English. I was convinced they . . .

His English was good enough not to use an interpreter?

Yes. I was convinced that they were really interested in a project with us and we were able to agree on enough things so we could sign [96] an agreement while we were there, and we were there less than a week. That's hard to do even with an English-speaking group. So I came back and I was very impressed with the situation. We went over again, or they came over here first, as I recall, and then I went back and took a larger group a year later. We were there over a week, and we had working groups and a whole bunch of things. Again, we were very successful at agreeing on things. There were some things we couldn't agree on, but we agreed that we couldn't agree and we agreed to work on those points. They generally needed more lead time than we do because they've got to go back to a bureau. They can't make any tentative agreements. They've got a little different problem than we have. I thought it [the Apollo-Soyuz Test Projects] was going to be a very good exercise for the two countries. I think we've got a lot to gain from it. I think it's going to work. I hadn't thought until this minute that I'd made those remarks about not being able to work with . . . But I sure did. I remember somebody got some poison pen letters of what's the matter with me, disagreeing with the President. Well, I didn't know that he was going to disagree with me.

You know who else didn't know? Webb didn't know, until the day before he made the speech, the 19th of September '63. He was making a speech in St. Louis, and in his prepared speech he had some sort of anti-Russian remarks. Well, he used them because they sold Congress. And he always used the Russians. But he changed his speech before he delivered it because he got a call from Washington saying the President's going to say this. So he was caught in it, too.

Why did you decide to leave MSC?

My wife [Jean] was ill, and I wanted to spend more time with her. I wanted to keep with NASA, but I wanted a job that was less demanding and where I could do what I felt I needed to do. She was ill and we wanted to have time to do a little traveling, visit people that we hadn't seen in a long time. The space program had been very demanding, and so that was the reason. I took this job because I thought I could do some good for NASA. At the same time, I didn't have to work every day. I had lots and lots of leave.

How long were you in that position [director of key personnel development]?

About a year, I guess. But I don't think I had that same title. I think I was a consultant to the administrator or something like that, for the others. I had this one for about a year.

Did you move directly back to [Houston]?

No. I resigned completely before we moved back here.

So you remained down in Houston.

Yes.

So both you and von Braun ended your careers at Headquarters.

But not being there. We reported to Headquarters, but did not live there.

I'd just like to ask you one last question, which is most open and general. As you look back on your career, which is quite a long and complex one, what do you see as the most satisfying part?

[98] I think the most satisfying thing to me is the memory of all of the years and the developments over those years, to have been an active participant in so many of the great things that the United States of America has done in aviation and in space flight. I can't pinpoint any one place that stands out . . . It's fun to look back, and it would be fun to have a more vivid memory of some of it. But I have enough memory to appreciate the opportunities that I've had and the fun that I've had participating in these things.

ENDNOTES

1. The Glennan-Webb-Seamans (GWS) Project for Research in Space History is a series of oral histories conducted by historians at the Smithsonian Institute's National Air and Space Museum. The role of management in NASA is explored through 193 hours of interviews with 22 individuals. These interviews examine various aspects of NASA's management practices in the Apollo program, taking a vertical slice through the organization from NASA's top management in Headquarters to management in the NASA Field Centers. A strategy of the GWS Project was to intensively interview (over 10 hours) key individuals to fully explore the ways in which management practices integrated scientific, technical, and political concerns. Complete copies of the transcripts from the GWS Project can be found on-line at: http://www.nasm.edu/naom/DSH/ohp-introduction.html#GWS. [link no longer valid, Chris Gamble, html editor]

2. Democratic Representative Albert Thomas of Houston was chairman of the House of Representatives Independent Offices Subcommittee of the Appropriations Committee.

3. The event referred to here actually occurred on September 17, 1963. Gilruth spoke at a luncheon meeting of the National Rocket Club in Washington. During his luncheon speech, Gilruth reacts to calls emanating from Congress for a joint lunar expedition by saying, "I tremble at the thought of the integration problems of a Soviet rocket with a U.S. spacecraft. . . when I think of the problems we have experienced with American contractors who all speak the same language." He goes on to say, "the proposal would be interesting and significant-but hard to do in a practical sort of way. . . but I'm speaking only as an engineer, not an international politician." David S.F. Portree, Thirty Years Together: A Chronology of U.S.-Soviet Space Cooperation (NASA Contractor Report 185707, NASA Johnson Space Center, February 1993), pp. 4.

4. On September 20, 1963, President Kennedy proposes a "joint expedition to the Moon" before the U.N. General Assembly. Ibid., p. 5

5. Soviet and U.S. space officials, led by Gilruth, met in Moscow October 26-28, 1970, to discuss joint space projects, including a common docking system. Three working groups [99] were established to further study the docking of a U.S. and Soviet spacecraft. David S.F. Portree, Thirty Years Together: A Chronology of U.S.-Soviet Space Cooperation (NASA Contractor Report 185707, NASA Johnson Space Center, February 1993), p. 12.

6. Academician Mstislav V. Keldysh, physicist and president of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.