SP-4223 "Before This Decade Is Out..."

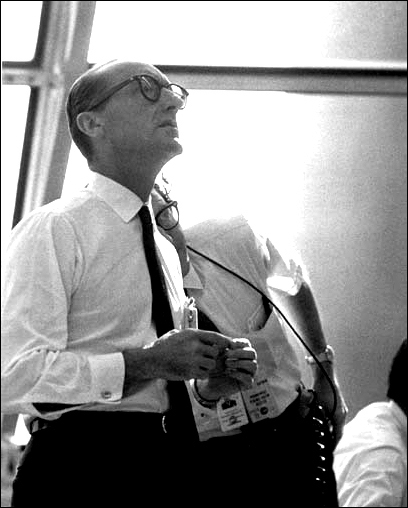

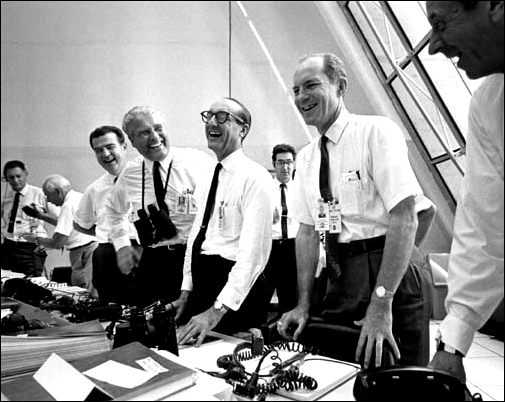

[100]

[101] During his six years of service at NASA, George Edwin Mueller introduced a remarkable series of management changes within the fledging agency during a time when strong leadership and direction were critical to its survival. Mueller joined NASA in September 1963 as deputy associate administrator for manned space flight, a position which soon changed its title in November of that year to associate administrator for manned space flight, a position he held until leaving the agency in 1969.

As associate administrator for space flight, Mueller worked with both the Gemini and Apollo programs and the three NASA centers devoted to manned space flight-Marshall Space Flight Center, Manned Spacecraft Center (now JSC), and Kennedy Space Center. Mueller worked to further the development of human space flight and to improve efficiency within NASA itself. Among his many accomplishments while at NASA was his desire for and receipt of an earlier flight schedule for the Gemini program. In addition, he successfully modified the testing of the Saturn V and the Apollo spacecraft from the previous comprehensive approach to the controversial "all-up" format. Mueller also requested that contractors send completed systems delivered to Cape Kennedy in order to minimize the need for rebuilding. Mueller implemented a concurrency program, which allowed a continued program development if something were to ....

[102]

....happen that seriously jeopardized the schedule. Also known as alternate paths, this program proved invaluable in the wake of the Apollo 204 fire. While workers were investigating the fire and making changes to the Apollo Command and Service Module, others were continuing development of the launch vehicle and the remaining spacecraft such as the lunar module. These changes saved time and money for the Apollo Program, which ultimately lead toward achieving President Kennedy's goal of landing a man on the Moon before the end of the decade.

After receiving his MS degree in electrical engineering from Purdue in 1940, Mueller began work at Bell Telephone Laboratories in New York City where he pursued research in video amplifiers and television links. After the U.S. became involved in WW II, Mueller began work on airborne radars and was soon transferred to Bell's laboratory at Holmdel, New Jersey, where he stayed for the next five years. Mueller left Bell in 1946 and became an assistant professor of electrical engineering at Ohio State University where he earned a Ph.D. in Physics in 1951.

[103] In 1955, Mueller began consulting with Ramo-Wooldridge (the predecessor of TRW) in the area of radar. At this time, Ramo-Wooldridge built missile guidance radars and Mueller was called upon to review their designs and troubleshoot potential problems. It was during this time that Mueller earned the reputation as a problem-solver and developed his theories regarding management that would serve him so well later in his career. Mueller held various positions during his five-year stay at Ramo-Wooldridge, which later became Space Technology Laboratories (STL).1 It was during his stay at STL that Mueller made his first contact with NASA while working on the design and construction of a series of lunar probes called Pioneer. While at STL, Mueller's achievements include the design, development, and testing of the basic systems and components of the Atlas, Titan, Minuteman, and Thor ballistic missile programs; development of other space-related projects such as Explorer VI and Pioneer V; and establishment of the U.S. Air Force tracking network for deep space probes.2

Mueller left NASA on December 10, 1969, to begin work as vice president of General Dynamics Corporation. In 1971, he joined System Development Corporation, a computer software company, where he served as chairman of the board and president until 1980 when he became chairman and CEO. He left in 1983 to become president of Jojoba Propagation Laboratories. Mueller began working for Kistler Aerospace in April 1995 where he remains director and CEO leading this privately held corporation's efforts toward developing a fully reusable multistage launch vehicle.

[104] Editor's Note: The following are edited excerpts from three interviews conducted with Dr. George E. Mueller. Interview #1 was conducted by Robert Sherrod on April 21, 1971, while Dr. Mueller was vice president of General Dynamics. Interview #2 was conducted by Sherrod on March 20, 1973, while Dr. Mueller was president of System Development Corporation. Interview #3 was conducted on August 27, 1998, by Summer Chick Bergen and assisted by Carol Butler of the Johnson Space Center Oral History Project.

Interview #2

. . . I'd like to get it straight on how many missions you really wanted to fly. Of course, you started out going on up through Apollo 20 before the last three were cut. I guess they were cut out after you had departed.

No. the decision was made to cut those out before I left . . . The real problem was the decision that was made to not continue producing the Saturn V, which was made first. Then the question was, since you weren't going to fly a great number of missions, how many should you fly? It turns out that the Houston people were concerned about the safety of flying out to the Moon and back and Bob Gilruth in particular wanted to limit the number of flights to the Moon. But I think that the real forcing function was the scientific community's desire to stretch the time interval between flights and you found that you were going to start flying equipment that was old and the cost of maintaining that equipment over long periods of time was quite clearly going to be high and so we tried to develop a program that would provide a continuing manned space program and bring on new equipment at as early a time as possible. So when we made up the integrated space program we took cognizance of the desires of the scientific community and we tried to arrange a program where there would be no significant gaps in manned space flight. So the plan that Vice President Agnew finally presented when President Nixon first came into office was a plan that we had developed in manned space flight which, among other things in order to conserve funds, we decided that Apollo 183 would be the last flight. Now I think that was a mistake because I was arguing for [105] a greater frequency of flights and therefore using more of the available hardware. The actual cost of flying these things was really very little. On the other hand, we also needed Saturn V's for the Skylab program and we needed to have at least two of them so that we had a back-up in the event the first one failed.

. . . As a general philosophy, you wanted to fly as few as possible before the landing on the Moon.

Exactly and for a very simple reason-it got you to the Moon quicker.

You wanted to make this deadline before the end of 1969.

Yes. And I particularly wanted to make sure that we kept the enthusiasm of the people up as we were going and to reduce the risks to an absolute minimum of failure before we got to the Moon and back. The more times you fly out there the more probability there is you won't come back.

I remember that you argued against the F mission-Apollo 10.

Yes.

Do you still think that it was unnecessary to fly it?

I think that we learned a fair amount on that flight. I suspect that we could not have done without it but on the other hand it was a worthwhile effort, particularly since the lunar module was far enough behind so it couldn't land. We needed to maintain the momentum of the program.

What about the C-Prime mission [Apollo 8], which they pulled on you while you were in Vienna. You were not very much in favor of this mission were you?

As a matter of fact, I was quite in favor of it. I thought it was a great idea. But, I used it as the mechanism for forcing, however, a very...

[106]

....careful review of the entire program. After all, it was the first time since the fire [Apollo 1] that I had people who wanted to do something who were pulling for progress. Prior to that time I had to provide all of the push . . . So I was able to take advantage of that and really force a very careful review of everything that went into [107] the success of that mission. I suspect that without such a thorough review, we might well have had problems downstream; you know problems that aren't immediately apparent tend to come back and bite you later. We made sure that we looked at everything that we could possibly think of that could go wrong and then made ourselves positive that if it did go wrong, we still wouldn't lose a crew.

Yes. However, the whole Apollo program would have gone down the drain if an oxygen tank had gone up on that mission and you didn't have the LM for a lifeboat.

Yes, although actually the most difficult mission in my view was still 501 [Apollo 4-the first launch of the Saturn V]. The whole Apollo program and my reputation would have gone down the drain if there had been an oxygen tank blow-up on 501. The whole concept of all-up testing, which made it possible to carry out the program, was in grave doubt up until 501.

Yes, that's the one that had to work.

Yes.

Although you wouldn't have lost any men on it if it did fail.

True enough, but you probably would have had a great deal of difficulty getting any man on one of those vehicles, too. Interestingly enough, 502 [Apollo 6] had everything in the world go wrong with it and if that had been 501, we probably would have had a great deal of difficulty proceeding . . . That also incidentally, was one of the reasons that I was so anxious to have a chance for a very thorough in-depth review of that program, which Apollo 8 provided us with.

To be retrospective, what about the scientists' argument? You remember in the summer of '69 particularly going into 1970, the scientists were making speeches, giving interviews, and writing articles about how there is no scientific aspect to the Apollo program.

[108] It's very interesting. About a year after the first landing, and after I was out of the program, one of the chief critics of the scientific content of the program came around and said to me, "You know, we sure made a mistake in not following your advice. We should have had these vehicles flying on three month centers. We would have learned so much more if we had more time on the Moon." Their argument was, "Gee, you need time to digest what you've learned." The fact of the matter is there is such a variety in the areas of the Moon that they weren't able to understand what they got from one area without having information from the other areas as well. So it wasn't until fairly near Apollo 17 that there was even a beginning of understanding of the lunar geology. Well, now that's an overstatement. Yet in a very real sense I believe that we would have had a much better understanding of the Moon, we would have ended up with a great deal more information if we had been able to fly those missions on three month centers and fly more of the vehicles.

Interview #1

. . . I understand that in the all-up testing, you were the one who really put it over in NASA. It was not yours originally, though. The Air Force had used it before, had it not?

We had introduced the concept at STL [Space Technology Laboratories] of all-up testing and I was involved in the development of that concept. It had been introduced in the Air Force although it was just about that time that it was first being tried . . . I had also introduced the concept of alternate paths so that in the event something went wrong with the Saturn V we could carry on the program in the Saturn I, or if something went wrong with the spacecraft, we could nevertheless carry on a limited program in developing the Saturn V. We had a number of alternates. We had a strategic plan of logical decision points and we used it.

In what case did you use it?

[109] For example, on the occasion of the fire, which slowed down the [development of] the spacecraft, we were able to continue the development of the launch vehicle and fly some early spacecraft in the unmanned mode which permitted us to move forward even though we were still making changes in the spacecraft to accommodate the fire problem. And we dropped out a number of things in the Saturn I program as a consequence. We freed up a lot of hardware because the Saturn V was successful. If the Saturn V had not been successful, we nevertheless could have developed a spacecraft on Saturn I's completely.

You said that after the fire you continued launch vehicle development. That means Apollo 4, 5, and 6. They weren't changed because of the fire were they?

They were rescheduled. We lost almost a year in that process. Because of that year we dropped out a series of unmanned flights on the Saturn I.

Who derived the strategy of making the Phillips Report a set of notes in the congressional hearings?4

I think it was either Jim Webb or me.

Jim says he didn't know what they were talking about until February 27, 1967.

I know he didn't know what they were talking about. Neither did I. I'll agree because I didn't think those notes or the report existed, so I was astonished when I got a copy of it.

You thought the notes had been written up, or the report had been written, but simply hadn't gone beyond one or two copies?

I thought they had been destroyed, again because they didn't appear to be constructive in terms of solving the North American problem. But we did pull out the constructive part, to give a series of briefings. [110] And we knew about that-I knew about that because I said, "I don't agree." I guess in all honesty I never saw the notes, read the notes, or read the report (except to look at one of two sections) . . . I told Sam [Phillips] that I didn't think they were appropriate then to publish and get into circulation. And I think that turned out to be a correct assessment. But on the other hand, we did have a good set of notes, which had been used to brief the people at North American and the people at NASA Headquarters. I guess in all honesty, I wasn't sure from the Mondale question, which is where this whole thing started, just what in the world he was talking about.5 I thought he was talking about something else. I couldn't quite relate-because he had the wrong date, among other things.

Yes, I think he said the summer of '65 instead of November or December. Mondale brought it up on February 27th and it lay dormant until April 11th when it came up in the Senate again.6 But on February 13th, just two weeks before the 27th, Jules Bergman7 saw a copy of it over at the Office of Manned Space Flight [at NASA Headquarters] and told Mondale about it....

Jules saw it in the Office of Manned Space Flight?

So he told me.

Well I'll be darned. I assumed he'd seen it out at North American . . . I'm surprised at that because I didn't know it existed at that time.

Somebody told him about it, and he called it the "Sam Phillips Report," which is what Mondale called it when it first came up.

You know, it may be interesting and fascinating like any other thing, but in terms of what we learned from it [the Apollo 1 fire] in future programs-we probably spent more time on it per unit information gained for doing better in the future by several orders of magnitude than on a whole host of other things that really made it possible to do the program.

[111]

Well, it caused a general tightening up throughout all of NASA and all of the contractors.

Yes, it took about two years to get it to the point where we could fly again with any reasonableness. And if you'll recall, I had to take the lead in convincing people that it was safe to fly and that we really couldn't afford not to take some risks, that there wasn't any way to fly any of these things without risk. And there was a whole year where nobody was willing to take any risk whatsoever.

Speaking of taking risks, I've seen this point made in only one place. Webb made it during his congressional testimony. He said, "I wonder now why we ever planned to fly the Block I spacecraft at all." Why was it-all of them were scrubbed except this one (Spacecraft 012-Apollo 1)?

[112] Well, it's a good question. In fact if you go back, you'll find that we almost scrubbed 012, and the reason we almost scrubbed it was that it wasn't clear that we were going to gain enough in flying it to make it worthwhile finishing it up. I was on the side saying "Well, I don't think the forward program will be helped enough by the extra effort required to build this-get it built and furnished in a way that it could fly-but what we ought to do is scrub it and do the next one right." However, Bob Gilruth and Joe Shea and the Houston people said, "No, we'll learn an awful lot by moving this thing on through, even though it isn't exactly the same configuration it clearly tests all of the equipment and all of the launch apparatus and so on, so we'll get that out of the way-that in the long run, will save us time rather than lose us time." And I went along with them because it was a valid argument. We had an agreement, however, that if it was going to slip any more, more than another couple of months, that we would in fact bypass it. None of us, of course, had any idea that this would pose any danger to the crew. We all thought that the thing was perfectly safe. And in fact it had been through design certification reviews which supposedly picked up these things. And one of the things that was asked was "Has this thing been examined for being fireproof?" You'll find in the record that there was a report prepared which said yes it met all of the needs for fire resistance.

I've heard it said about the 204 fire hearings that you and Webb disagreed on how to testify. Your idea was to get the hearings over with and get on with business, and Webb knew or felt that NASA had to wear this "hair shirt" with a "mea culpa" attitude. Is this a fair statement?

I think it's a fair statement. Jim, who's had much more experience in this area than I did, felt that it would take a number of months for all of the facts to filter up to the surface. And if we finished the hearings too soon and then further facts were developed, you'd be terribly vulnerable to being accused of whitewashing a terrible situation. He wanted the hearings to last long enough so that every single fact that could be deduced was in fact brought to the surface.

[113] He trotted out so everybody could see it and understand it and everything hidden turn up. That strategy surely worked. It was helpful, because it took two months for some of the things that were lurking in people's minds to come out. I guess the hearings themselves lasted four months, and that seemed a bit long-winded. In one other area, I guess with respect to the Phillips Report, we did disagree. The minute I discovered the Report, I told Jim about it and we were both concerned and disturbed because in good faith, we told the Senate committee that we didn't know of any Phillips Report, and then here is this report on North American Aviation signed by Sam Phillips. And that was, I guess, two weeks after Mondale's question [during the February 27 hearing] when this thing came to light. That's why you astonished me when you said Jules Bergman said he saw it at the Manned Space Flight Headquarters.

How did you and Webb disagree?

I felt that we needed to protect the contractor from a full disclosure of the material in that report. Not because it was North American but because of the whole process. This kind of management review depends upon finding out what the truth is and you can only find that from the contractor and he had given it to them in confidence so we ought to keep it in confidence. So that was my initial reaction, and Sam Phillips felt very strongly about it . . . But at that time we didn't know, had no idea, how much was known about this. About two or three days later I had a chance to talk with Jim Gehrig8 (Jim Gehrig asked me and I told him about these notes). So then we had a long discussion about how it would be better to summarize it, give a summary to the committees so they would have it available. We made the whole report available to Tommy Thompson [Thomas H. Thompson, director, Apollo Systems Engineering] as soon as we discovered it, so they had it for their review.

Of course you know that when Gehrig first found out about it he asked the General Accounting Office (GAO) for it-that's how it got bound up and labeled with "Report" on the front at that time.

No. The GAO got it before Mondale ever brought it up. That surprised me when I learned it.

Really?

Yes.

I didn't know that.

I think it was about February 17.

Before Mondale raised the question?

Before Mondale raised the question. I think Gehrig himself asked the GAO to look into it.

You may be referring to the second time that Mondale asked the question.

No. I'm talking about the first time. Before February 27, 1967, when it first came up in the Senate.

The GAO then knew more than Jim Webb or I did.

Interview #3

. . . Why did you decide to leave NASA and go back to industry?

Well, several reasons. One is that the decision had been made to terminate the Apollo program, and that was a good time then to leave before, and let someone else take over for the next phase. From a practical point of view, I needed to go make some money so I could keep my family going. It was costly for us to join the Apollo program. My salary was half what I was making in industry [115] when I went there, and it was just a strain to keep the family going and work going at the same time. So I went back to industry.

It was nice to leave with the triumph of landing on the Moon.

Well, it was a good time to leave in that sense. You know, it looked like it would be another 5 or 10 years before the next program was going to come to fruition. There's also the general thing that if you stay in Washington long enough, if you do anything, you create enough enemies to make it difficult to get anything done. I'd left before I think I created that set of enemies, but it's clear that you have a limited time of effectiveness in Washington if you really are doing anything. If you're not doing anything, you can stay there indefinitely.

END NOTES

1. STL [Space Technology Laboratories] was originally a spinoff of Ramo-Wooldridge in 1959 and later became part of Thompson-Ramo-Woolridge (TRW). STL was a corporate think tank that supported the Air Force Ballistic Missile Program. In 1960, a group from STL broke away and formed the Aerospace Corporation. In 1966, STL was renamed TRW Systems group. Courtney G. Brooks, James M. Grimwood, and Loyd S. Swenson, Jr., (NASA SP-4205, 1979), p. 200.

2. Henry C. Dethloff, Suddenly, Tomorrow Came: A History of the Johnson Space Center, The NASA History Series (Houston: NASA, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, 1993), 101; George Mueller, interview by Howard E. McCurdy, June 22, 1988, transcript, NASA Historical Reference Collection, NASA Headquarters History Office, Washington, D.C.; Interview by Martin Collins, July 27, 1987; Henry C. Dethloff, Suddenly, Tomorrow Came: A History of the Johnson Space Center, The NASA History Series (Houston: NASA, Lyndon B. Johnson Space Center, 1993), 101; Dr. George Mueller, interview by Martin Collins, February 15, 1988, transcript, NASM Oral History Project, [NASM Homepage], [Online], (September 6, 1996-last updated), available at http://www.nasm.edu/NASMDOCS/DSH/TRANSCPT/MUELLER.HTML [July 2, 1998-accessed]. [link no longer valid, Chris Gamble, html editor]

3. (Editor's note: Uncertain of Mueller's reference to Apollo 18 as being the last flight and feel that he is actually referring to Apollo 17) By 1970, NASA began canceling later Apollo flights, specifically, Apollo missions 18-20. On January 4, 1970, NASA Deputy Administrator George M. Low told the press that Apollo 20 had been canceled. On September 2, 1970, NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine announced at a [116] Washington news conference that Apollo missions 18 and 19 would be canceled because of congressional cuts in Fiscal Year 1971 NASA appropriations. Remaining missions were then designated Apollo 14 through 17. UPI, "Apollo Missions Extended to '74," New York Times, Jan. 5, 1970, p. 10; NASA Administrator Thomas O. Paine in NASA News Release, "NASA Future Plans," press conference transcript, Jan. 13, 1970; "Statement by Dr. Thomas O. Paine," Sept. 2, 1970; Astronautics and Aeronautics, 1970 (NASA SP-4015, 1972), pp. 248, 284-85.

4. After the Apollo 1 fire, a review board was established on January 28, 1967, by Jim Webb and NASA Deputy Administrator Robert C. Seamans, Jr. Webb and Seamans asked Floyd L. Thompson, director of NASA's Langley Research Center, to take charge as chairman of the Apollo 204 Review Board. On November 22, 1965, at Mueller's request, Apollo Program Director General Samuel C. Phillips, initiated a review of NASA's contract with North American Aviation to determine why work on the Apollo Command and Service Module (CSM) and the Saturn V second stage (S-II stage) had become so far behind schedule and over budget. On December 15 of that same year, Phillips provided a set of notes which comprised their review to North American Aviation President J. Leland Atwood. These notes, which were highly critical of North American's performance on the Apollo program, later became known as the "Phillips Report" during the Apollo 204 fire investigation. The Phillips Report took on added significance and became highly controversial during the 204 fire investigation hearings when it was revealed that NASA Administrator James Webb was apparently unaware of the existence of the report. John M. Logsdon, editor, Exploring the Unknown Volume II: External Relationships (NASA SP-4407, 1996), pp. 527-538.

5. On February 27, 1967, NASA officials testified in an open hearing of the Senate Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences on the Apollo 204 fire. It was during this time that Senator Walter F. Mondale, one of the Senate Committee members, first introduced the Phillips Report while raising questions of negligence on the part of NASA management and the prime contractor North American Aviation. It was during this time that Webb and others on the NASA review board expressed doubt and confusion as to which report Mondale was referring.

6. On April 11, the Senate held another hearing before the Committee on Aeronautical and Space Sciences concerning the Apollo 204 fire.

7. Jules Bergman was a reporter for ABC and extensively covered the manned space program for ABC News through to the space shuttle program.

8. James J. Gehrig, Senate staff director.